Development of the private hospitals in Singapore from 1983 to 2022

Introduction

In recent years, the global healthcare landscape has witnessed significant transformations, with governments striving to enhance healthcare access and quality through diverse strategies. Among these approaches, the development of the private hospital sector has emerged as a critical aspect of healthcare policy in many countries due to constraints in public health expenditure and growing needs of the middle- and higher-income population.

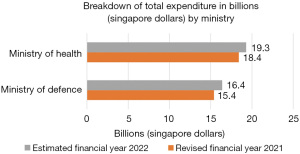

In Singapore, healthcare expenditure has overtaken defense spending in 2022 as shown in Figure 1 (1). This represents a year-on-year increase of $0.9 billion (4.9%) and accounts for approximately 3.4% of Singapore’s gross domestic product (GDP). This is a sharp contrast to earlier years where healthcare spending was relatively lower (0.9% of GDP in 2006) (2) compared to other national priorities. To achieve this increased spending in healthcare expenditure, Singapore has raised consumption tax on most goods and services from 7% to 8% in 2023 and 8% to 9% in 2024.

The importance of understanding the Ministry of Health’s (MOH’s) role in nurturing the private hospital sector lies not only in its implications for the domestic healthcare system but also in the lessons it offers to the global healthcare community. By exploring the interplay between public and private healthcare providers, resource allocation strategies, and the impact on patient access and outcomes, this analysis promises valuable insights for healthcare policymakers, researchers, and industry stakeholders beyond Singapore’s borders.

Furthermore, as the private hospital sector’s growth can have substantial economic ramifications, including job creation and contributions to the GDP, this investigation carries relevance for economic analysts and policymakers seeking to comprehend the intricate relationship between healthcare and national development.

Singapore’s status as a renowned medical tourism destination adds another dimension to the MOH’s initiatives. Understanding how the government’s support and regulatory framework facilitate the country’s attractiveness as a medical tourism hub holds significant potential for other countries aspiring to capitalize on this burgeoning market.

In light of these wide-ranging implications, this paper seeks to present a comprehensive analysis of the MOH’s role in the development of the private hospital sector, providing a valuable contribution to the discourse on healthcare policy and administration on both regional and global scales. Through this exploration, we aim to shed light on the dynamics that underpin a successful public-private healthcare partnership, offering invaluable insights for enhancing healthcare systems worldwide.

Methods

Theoretical framework

The healthcare landscape in many nations is increasingly influenced by the Developmental State Theory (3), a prominent approach in shaping public policies and fostering economic development. Briefly, the theory posits that government actively intervene in the economy to facilitate industrialization, technological advancement, and social progress.

Data collection and sources

Data for this analysis are sourced from various governmental reports, academic studies, policy documents, and industry publications.

Methodology

The analysis employs a qualitative approach, combining document analysis and thematic synthesis. Government reports and policy documents are critically reviewed to identify the MOH’s explicit roles and actions in nurturing the private hospital sector. The thematic synthesis involves identifying recurring themes and patterns in the data, categorizing them according to the MOH’s roles, and establishing connections to the Developmental State Theory.

Data interpretation

The identified themes are interpreted within the context of the four roles of the state: custodian, demiurge, midwifery, and husbandry that are used by political economist Peter Evans (3).

- Custodian: regulator, enforcement of contracts and protecting property rights;

- Demiurge: direct producer of goods and services, e.g., state-owned enterprises;

- Midwifery: provider of support and assistance to private businesses;

- Husbandry: promoter of growth of private businesses.

Limitations

This analysis is limited by the availability and reliability of the data sources. The accuracy of the findings is contingent on the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the government reports and industry publications.

Results

This section discusses the characteristics of the private tertiary healthcare sector in Singapore. As of 22 October 2022, there are 17 acute hospitals, of which 9 are “public”, and 8 are private (7 “for-profit” and 1 is “not-for-profit”) (refer to Table 1). The sector is capital-intensive, with large amounts of investment needed to build and operate an acute hospital. For example, the estimated cost of building Sengkang General Hospital (1,400 beds) was $904 million in 2014 (4), and the last private hospital, Farrer Park Hospital (220 beds), was estimated to cost $800 million to build in 2016 (5). Additionally, medical equipment has a useful life of 8 to 10 years, but constant updates are necessary to remain competitive, which requires ongoing capital.

Table 1

| Forms of organizations | Hospitals | Year opened | Estimated number of beds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | |||

| National Healthcare Group | Tan Tock Seng Hospital | 1844 | 1,700 |

| Khoo Teck Puat Hospital | 2010 | 795 | |

| SingHealth | Singapore General Hospital | 1821 | 2,000 |

| KK Women’s and Children Hospital | 1858 | 848 | |

| Changi General Hospital | 1998 | 1,043 | |

| Sengkang General Hospital | 2018 | 1,000 | |

| National University Health System | Alexandra Hospital | 1938 | 326 |

| National University Hospital | 1985 | 1,239 | |

| Ng Teng Fong General Hospital | 2015 | 700 | |

| Total public beds (% of total beds) | 9,651 (82.23) | ||

| Private | |||

| For-profit | |||

| Parkway Hospitals | Parkway East Hospital | 1942 | 143 |

| Gleneagles Hospital | 1957 | 257 | |

| Mount Elizabeth Hospital | 1979 | 345 | |

| Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital | 2012 | 333 | |

| Raffles Medical Group | Raffles Hospital | 2002 | 380 |

| Thomson Medical Group | Thomson Medical Centre | 1979 | 187 |

| Farrer Park Company | Farrer Park Hospital | 2016 | 121 |

| Total for-profit beds (% of total beds) | 1,766 (15.05) | ||

| Not-for-profit | |||

| Mount Alvernia | Mount Alvernia Hospital | 1961 | 319 |

| Not-for-profit beds (% of total beds) | 319 (2.72) | ||

| Total beds | 11,736 |

In terms of differentiation, the private tertiary healthcare sector is not highly differentiated, except for one “public” hospital that specializes in women’s and children’s health. Still, it competes with ten other “public” hospitals and private hospitals (6). The private acute hospital sector offers better facilities and the latest medical technology compared to the public sector and neighboring countries.

The private tertiary healthcare sector is highly complex and interacts with other sectors. For example, Raffles Medical Group (RMG) has a health insurance subsidiary that provides coverage for tertiary care (7) and a network of family medicine clinics (private primary care) that refers patients to be admitted to Raffles Hospital. The sector is highly regulated by the MOH, and the high barriers to entry make it challenging for newcomers to understand the laws and regulations before opening a new acute hospital in Singapore (8).

Trade in healthcare services can be divided into four types, with consumption abroad being the most relevant to the private tertiary healthcare sector. Private acute hospitals attract patients from neighboring countries to seek tertiary healthcare in Singapore, providing revenue for both public and private acute hospitals and stimulating the local economy. Telemedicine makes it possible to monitor patients remotely, and preadmission consultations and post-discharge follow-ups can be conducted in their home countries.

In summary, the private tertiary healthcare sector is capital-intensive and highly complex. The government or the private sector is best suited to provide this type of service, with not-for-profit organizations playing a secondary role. It is not highly differentiated and not very tradeable, making it suitable for “local services” and “infrastructure” (9). The government should set ground rules and direction, and the private sector should provide the service, as discussed next.

Role of MOH

The MOH’s role in Singapore, a developmental state (10), involves extensive government intervention in economic policy to promote industrialization, with a narrow focus on GDP growth and surplus accumulation as a dominant one-party government (11). The National Health Plan of 1983 communicated to the private sector that new private hospitals were welcomed to provide the public with more options. Furthermore, the liberalization of Medisave in 1985 allowed working individuals to contribute part of their monthly salaries to pay for personal or immediate family’s hospitalization bills, initially only for use in government hospitals, but later extended to cover bills incurred in private hospitals. This move can be seen as an example of the government’s role as a “husbandry”, providing an even playing field for private hospitals.

Health Corporation of Singapore [1987]

To reduce the government’s budget requirements, a new government-owned structure was established to acquire and manage all government hospitals with a focus on cost recovery (increasing from 15% to 55%) (12). This has resulted in a blurring of the concept of “public” hospitals, and the government’s role has shifted to a “demiurge” role in providing private tertiary healthcare services to cross-subsidize non-private patients and set a benchmark for private hospitals. Commercial accounting systems were introduced to promote better costing and discourage overspending in “public” acute hospitals, while annual grants are given to provide subsidized care for patients who cannot afford private services. At the same time, private services are also offered in “public” acute hospitals for patients who are willing to pay more for better facilities, although MOH maintains that quality of care is similar between private and subsidized patients (13).

White Paper on Affordable Health Care [1993]

The private sector’s share of acute hospital beds increased from 15% to 20% between 1983 and 1993, with a target of 30% by 2010 (14). To encourage the private sector to play a larger role, the government would adopt a “husbandry” role by limiting the number of private beds in “public” hospitals (9% of total beds and 35% in each public hospital). The government would also play a “midwifery” role by releasing land parcels for private hospital development and encouraging transnational capital to build private hospitals. An example is the Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, owned by Mitsui & Co (Japanese), and Khazanah Nasional (Malaysia) (15). MOH would also play a “custodian” role by limiting balance billing by private hospitals of Medisave patients to keep healthcare “affordable”, even in private acute hospitals.

Medishield Plus [1994]

Medishield, a prepaid insurance plan for major medical expenses with high deductibles and co-payments to keep premiums low, was introduced in 1990 (16) to cover hospitalization bills in subsidized wards. In 1994, the government introduced Medishield Plus, which had higher premiums and allowed patients to stay in private hospitals due to higher coverage. The government played a “husbandry” role in this instance, as private hospitals could now admit patients with Medishield Plus.

Singapore Medicine [2003]

In 2003, the Healthcare Services Working Group (HSWG) of the Economic Review Committee set a goal for Singapore to treat one million foreign patients by 2012. This led to the launch of Singapore Medicine, a multi-agency initiative involving the Singapore Tourism Board, Economic Development Board, and International Enterprise Singapore to promote Singapore as an international medical hub. The government’s role in this initiative is that of a “husbandry” as it involves a coordinated effort to market Singapore’s private tertiary healthcare to neighboring countries. However, MOH was not directly involved in this initiative as there may be conflicting goals between promoting tourism and keeping healthcare affordable for Singaporeans.

Publishing Hospital Bills [2003]

In a joint initiative with the Consumers Association of Singapore, MOH published statistics on hospital bills for the 28 most common diseases on its website. This helped to reduce information asymmetry between patients and hospitals and led to lower average, median, and 90th percentile bill sizes for B2 and C ward classes.

Competition Commission of Singapore [2007]

Established in 2005, the Competition Commission of Singapore administers and enforces the Competition Act 2004. In 2007, the Singapore Medical Association withdrew its Guideline on Fees due to concerns that it may contravene Section 34 of the Competition Act. This resulted in private specialists being able to charge as much as the market could tolerate, leading to an increase in private tertiary healthcare services and medical inflation. The government’s role is that of a “custodian”, but in this case, regulation was reduced even though fees guidelines were voluntary. Market failure in healthcare means that competition may not necessarily drive down costs in the private tertiary services as specialists compete based on quality and not cost. In 2018, fee benchmarks for 222 common surgical procedures by private surgeons were published online to boost transparency and provide signaling to private surgeons not to charge above the benchmark without good reasons.

In 2018, the MOH instructed public hospitals to stop actively marketing themselves to foreign patients and to discontinue the practice of paying agents to bring in foreign patients. This decision was made as part of the government’s role as a “custodian”, and its impact was a reduction in the number of foreign patients seeking treatment in public hospitals, indirectly encouraging them to use private hospitals instead.

To reduce moral hazard and unnecessary treatment, MOH mandated a minimum of 5% co-payments for private insurance plans in 2018. This decision was made as part of the government’s role as a “custodian”, and it has had the effect of reducing revenue growth in private tertiary medical services. However, it has made growth in this sector more sustainable, as concerns had been raised that Singapore’s private tertiary healthcare services were becoming unaffordable, even for medical tourists (17).

In 2020, MOH ordered Concorde International Hospital, a private hospital, to suspend its services due to lapses that posed a risk to patient safety. This decision was made as part of the government’s role as a “custodian”, and it demonstrates its power to prevent private acute hospitals from operating if they fail to meet the necessary safety standards (18).

Role of private sector

There are two major healthcare providers in Singapore, RMG, and Parkway Hospitals, with different operating models. RMG employs specialists to reduce supplier-induced demand due to information asymmetry, while Parkway Hospitals prefers specialists to be independent contractors, partnering with them as needed.

RMG was founded in 1976 and has grown to offer tertiary care at Raffles Hospital.

An example of public-private partnership is the Emergency Care Collaboration between RMG and MOH to provide subsidized healthcare for eligible patients sent by ambulance.

Private healthcare providers employ healthcare professionals trained by public hospitals, who can be considered public goods.

Doctors trained in local medical schools have to serve a service obligation with public hospitals, with basic and specialist training provided by these hospitals. Private hospitals can hire these specialists with higher salaries, but they are no longer able to serve subsidized patients. This also applies to other healthcare professionals.

The insurance industry also plays a role in developing the private tertiary healthcare sector by allowing policyholders to purchase additional insurance or riders to cover co-payments and deductibles, leading MOH to insist on a minimum 5% co-payment to reduce moral hazard.

Role of business associations in Singapore healthcare

The Singapore Medical Association (SMA) represents medical practitioners in both public and private sectors since its formation in 1959. However, only 10.9% of registered medical practitioners were listed on its online directory in 2021, implying low membership density (19). The SMA’s role is to advocate, maintain ethics and professionalism, continue professional development, and foster collegiality among doctors. It enables doctors to inform their departure from “public” hospitals, provides information on available clinic spaces, and offers seminars to doctors considering a move to the private sector.

The Academy of Medicine, established in 1957, provides postgraduate specialist training for medical and dental specialists. It has a higher membership density of 56.5% out of 6,431 medical specialists in 2021. The Academy’s primary role is to provide professional guidance and advice to the MOH on clinical standards, the manpower projection required to staff public and private hospitals in Singapore, and the suitability of health technology allowed in Singapore. The Academy’s recommendations impact the services that the private tertiary healthcare sector can provide.

The Healthcare Services Employees’ Union standardizes the salaries of healthcare professionals, except doctors, through collective agreements between “public” hospitals. This prevents poaching of staff by offering higher salaries, but it reduces competition. Some healthcare professionals have moved to the private sector in search of higher salaries and better working conditions, even though the public sector recently increased nurses’ salaries by up to 14% to reduce staff turnover (20).

Discussion

As nations grapple with the escalating costs of healthcare, Singapore’s shift towards prioritizing healthcare expenditure offers valuable insights. The evolution from minimal healthcare spending to a considerable share of GDP underscores the imperative of resource allocation to meet burgeoning demands. This is especially relevant as countries strive to strike a balance between robust healthcare systems and sustainable fiscal policies.

Singapore’s public-private healthcare partnership model merits consideration. The MOH’s role as a regulator, promoter, and provider underscores the complexities of orchestrating a harmonious ecosystem where private hospitals complement public services. This symbiotic relationship serves as a reference for nations seeking to enhance patient access while leveraging private sector efficiency and innovation.

The economic ripple effects of the private hospital sector’s growth—such as job creation and GDP contribution—are pivotal in a holistic assessment. Singapore’s case reflects the potential of healthcare as an economic catalyst. Balancing economic aspirations with equitable healthcare access necessitates careful navigation, encapsulating a broader discourse on developmental policies and sector-specific growth.

The trajectory of Singapore as a medical tourism hub underscores the intricate ethical considerations at play. While showcasing the nation’s medical prowess, this phenomenon raises questions about equity and accessibility. Policymakers must grapple with maintaining a global reputation while ensuring that domestic healthcare needs are met equitably.

The application of the Developmental State Theory to healthcare policy resonates as an innovative approach. Singapore’s MOH embodies the state’s active role in fostering a conducive environment for healthcare innovation and evolution. This resonates with the ongoing debate over government intervention’s efficacy and limits, impacting the global discourse on public goods provisioning.

In the backdrop of public-private synergy, the regulatory landscape assumes paramount importance. Striking a balance between promoting private sector growth and safeguarding equitable access to healthcare poses formidable challenges. The lessons learned from Singapore’s regulatory strategies offer valuable considerations for navigating similar dilemmas worldwide.

Anticipating the future trajectory of Singapore’s healthcare policy requires acknowledgment of technological advancements and evolving demographics. Amidst the rise of telemedicine, shifting disease profiles, and an aging population, Singapore’s response provides insights into adapting policy frameworks to address evolving healthcare paradigms.

Conclusions

Singapore’s approach to developing the private hospital sector offers valuable lessons for countries considering healthcare privatization. The harmonious interaction between public and private healthcare, guided by a multifaceted government role as regulator, promoter, and provider, showcases a potential blueprint. This model demonstrates the importance of maintaining a delicate equilibrium between economic growth and equitable healthcare access, while transparent regulations and adaptive policies are essential to prevent imbalances. However, challenges arise in ensuring accessibility, managing technological advancements, and addressing demographic shifts. Singapore’s experience underscores the significance of a well-calibrated public-private partnership in healthcare and provides a valuable reference for countries navigating similar healthcare policy deliberations.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Francis Hutchinson (Adjunct Faculty, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore) for his invaluable guidance. This work is an extension of the assignment for his class “Business and Public Policy” during my master’s in business administration at Nanyang Technological University.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-23-62/prf

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-23-62/coif). The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ministry of Finance Singapore. Analysis of revenue and expenditure. Financial year 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.mof.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider3/budget2022/download/pdf/fy2022_analysis_of_revenue_and_expenditure.pdf

- Data.gov.sg. Government Health Expenditure. 2019. Accessed 1 August 2023. Available online: https://beta.data.gov.sg/datasets/479/view

- Evans PB. Embedded autonomy: States and industrial transformation. 1st ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1995.

- Nikkei Asia. Penta-Ocean wins major contract for Singapore hospital. 2014. Accessed 9 April 2023. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Penta-Ocean-wins-major-contract-for-Singapore-hospital

- Healthcare. Farrer Park Hospital is in the realm of disrupting the healthcare norm. 2020. Accessed 9 April 2023. Available online: https://healthcare-digital.com/company-reports/farrer-park-hospital-realm-disrupting-healthcare-norm

- The Best Singapore. Complete Guide to Hospitals to Give Birth in Singapore 2023. 2023. Accessed 9 April 2023. Available online: https://www.thebestsingapore.com/living/complete-guide-to-singapore-hospitals-to-give-birth/

- Raffles Health Insurance. About Us. 2022. Accessed 9 April 2023. Available online: https://www.raffleshealthinsurance.com/resource-centre/about-us/

- Singapore Statutes Online. Private Hospitals and Medical Clinics Act 1980. 2020. Accessed 9 April 2023. Available online: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/PHMCA1980

- Manyika J, Mendonca L, Remes J, et al. How to compete and grow: A sector guide to policy. San Francisco: McKinsey Global Institute; 2010.

- Siddiqui K. A study of Singapore as a developmental state. In: Kim YC. editor. Chinese Global Production Networks in ASEAN. Cham: Springer; 2016:157-88.

- Tan KS, Bhaskaran M. The role of the state in Singapore: Pragmatism in pursuit of growth. The Singapore Economic Review 2015;60:1550030. [Crossref]

- Phua KH. Attacking hospital performance on two fronts: network corporatization and financing reforms in Singapore. In: Preker AS, Harding A. editors. Innovations in health service delivery: the corporatization of public hospitals. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2003:451-85.

- Ministry of Health Singapore. Singapore's Healthcare System. 2018. Accessed 10 April 2023. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sg/home/our-healthcare-system

- Ministry of Health Singapore. Affordable Health Care. 1993. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sg/resources-statistics/information-paper/affordable-health-care-(1993-white-paper)

- IHH Healthcare. Top 30 Shareholders. 2023. Accessed 9 April 2023. Available online: https://www.ihhhealthcare.com/investors/shareholders/top-30-shareholders

- Reisman DA. Medisave and Medishield in Singapore: Getting the Balance Right. Savings and Development 2006;30:189-215.

- Sendingan S. Singapore's staggering healthcare costs may be pushing medical tourists away. 2018. Accessed 10 April 2023. Available online: https://sbr.com.sg/healthcare/in-focus/singapores-staggering-healthcare-costs-may-be-pushing-medical-tourists-away

- Channel News Asia. Concord International Hospital ordered to suspend all healthcare services due to ‘significant lapses’. 2020. Accessed 10 April 2023. Available online: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/concord-international-hospital-suspend-services-lapses-moh-505326

- Singapore Medical Council. Singapore Medical Council Annual Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider2/publications-newsroom/smc-annual-reports/smc-annual-report-2021.pdf

- Lai L, Begum S. Budget debate: Pay hikes for over 56,000 public healthcare workers from July; nurses get up to 14% more. 2021. Accessed 9 April 2023. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/higher-salaries-for-more-than-56000-public-healthcare-workers-from-july

Cite this article as: Ang YG. Development of the private hospitals in Singapore from 1983 to 2022. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2023;7:11.