Hospitals and community benefit requirements: perspectives of community benefit administrators in Massachusetts

Introduction

Nonprofit hospitals in the United States are considered “charitable institutions” (1), and thus are exempt from paying federal, state and local taxes. In 2011, national inpatient hospital costs (both for-profit and nonprofit hospitals) equaled $387 billion, while the value of tax-exemptions and charitable gifts to nonprofit hospitals was estimated to exceed $24.6 billion (1,2).

Numerous studies have raised questions whether nonprofit hospitals provide sufficient community benefits to justify these exemptions (3-5). This has prompted closer scrutiny of hospitals’ provision of community benefit and the adoption of policies for ensuring greater hospital accountability and transparency for the types and amounts of benefits provided (6-9).

As such, nonprofit hospitals find themselves in an era of increased scrutiny with respect to their obligation to provide community benefits. Although research indicates that nonprofit hospitals have made some progress in meeting the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) requirements for addressing community health needs, there has been little investigation of how hospitals are organizing and managing their community benefit programs to address the growing challenges and changing regulations that they now confront (4,10-13).

Accordingly, we conducted a pilot study as a mean to gain some insight as to how hospitals are managing their community benefit programs. We focused on individuals with the day-to-day responsibility of managing hospital community benefits [henceforth referred to as community benefit administrators (CBAs)] in hospitals in Massachusetts where in 2018 the Attorney General updated the guidelines pertaining to community benefit oversight (9). In Massachusetts, 2011 total inpatient hospital costs were just over $9 billion and estimated 2011 tax-exempt values were approximately $1.3 billion, higher than any state in the U.S. (1,6,14). We conducted our qualitative study to address three key questions related to nonprofit hospital community benefits: (I) what are some examples of hospital organizational structures that support community benefits operations (II) what are the potential barriers that nonprofit hospital CBAs experience in the face of changing requirements? and (III) how do CBAs see their role within the hospital and within the community? Our hypothesis, based on classic organizational theory, was that community benefit departments situated at more senior levels may have more visibility and influence within the hospital, and therefore, garner more of the hospital’s focus on community benefit activities (15,16).

Federal policy

Federal policy on nonprofit hospital tax status and the requirement to provide community benefits has undergone significant changes over time. In 1956, the Internal Revenue Services (IRS) tied charity care requirements to nonprofit status eligibility and required such hospitals to provide “as much charity care” as the hospital could afford (17).

The landmark Medicare and Medicaid Bill of 1965 expanded insurance coverage for seniors and the poor, and thus was expected to diminish the need for charity care required from hospitals. An IRS Revenue Ruling issued in 1969 expanded possibilities for nonprofit hospitals to qualify for tax exemption beyond previous definitions (18). This was an attempt to move hospitals away from defining community benefits (CB) solely as “charity care” (18,19). However, in the intervening 40 years, there has been ongoing conflict between consumers, regulators and hospitals on how much hospitals should be spending in lieu of paying taxes. Congressional inquiries led to a renewed focus on nonprofit hospital behavior that led the IRS to adopt Form 990, Schedule H in the mid-2000s. Nonprofit hospitals are now required to complete Schedule H annually, detailing how much they spend for pre-defined categories of community benefits such as charity care and means tested government programs, community health improvement, health professionals education and research (12,20).

However, the largest and arguably most impactful development to nonprofit hospital community benefit activities was the 2010 Affordable Care Act. Under Section 9007 of the ACA, nonprofit hospitals are required to establish and publicize financial assistance policies, limit charges and aggressive billing practices, improve emergency service policies, and conduct a community health needs assessment (CHNA) with implementation strategy once every 3 years (21).

As part of conducting the community health needs assessment, the ACA requires that nonprofit hospitals must define the community they serve, assess the needs of that community by soliciting input from persons who represent the interests of the community (including those with public health knowledge), and document identified needs in a publicly available report (22). Once the community health needs assessment report is final, it is required to be posted publicly. If a hospital plans to address the health need, it must document anticipated actions and associated impact, resources, and planned collaborations for these efforts as part of a publicly available implementation strategy document (21,22). Hospitals can identify significant community needs that they are not planning to address due to lack of resources, expertise or effective interventions (22).

While recent research has shown that nonprofit hospitals have moved forward with conducting required community health needs assessments, the degree of hospital compliance with all ACA requirements is more questionable (10,23). In particular, a recent study showed that although 99% of hospitals report completing a CHNA and an implementation strategy—only 60% of hospitals had both documents available on their website as the law requires (10). Additionally, the study reports that up to 40% of hospitals missed key requirements (10).

State/local policy

Many papers on nonprofit hospital community benefit regulations have focused on federal regulations; however, state, and local governments often have their own expectations pertaining to hospitals’ provision of community benefits (4,23-26). The Hilltop Institute’s “Community Benefit State Law Profiles” report on the varying levels of state community benefit laws. In their most recent update, Hilltop identified 25 states as having at least one community benefit requirement, with Massachusetts being relatively light on requirements at the time (pre-Attorney General update) (27). The most stringent level of state community benefit regulation is setting a minimum spending threshold for nonprofit hospitals specific to community benefits; however, only five states have implemented this level of regulation (27).

The state of Massachusetts recently revised their nonprofit hospital community benefit guidelines through the Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office. The latest revision, drafted in 2018 for implementation in 2019, increased transparency and accountability for Massachusetts’ hospitals. While the Attorney General guidelines are not required by Massachusetts General Law, the fact that they are promulgated by the Attorney General carries force, therefore, we consider and refer to these guidelines as requirements.

Per the Massachusetts Attorney General Guidelines, all hospitals should clearly demonstrate support for community benefit implementations strategies at the highest governing levels (hospital governing board and senior management) (9). The Attorney General also encourages hospitals to have a “Community Benefit Leadership Team” comprised of hospital leaders and operational staff (such as social workers and health educators) to partner with community benefit department staff (28). The Attorney General encourages hospitals to have Community Benefits Advisory Boards whose role is to bridge the hospital to community leaders and should include members of the community that reflect the population to be served by the hospital. These boards can make recommendations to the Community Benefit Leadership Team.

From an implementation perspective, the 2018 guidelines increase the amount of community engagement required by hospitals and call for more detailed assessments of where community benefit dollars are being spent relative to identified health needs (9). The 2018 guidelines encourage collaboration and regional planning, direct hospitals to focus on key priorities at a state level, encourage best practices, and expect hospitals to “self-assess” their community engagement efforts (see Table 1 for the Community Benefit Principles) (9,23,29). The updated Massachusetts Attorney General guidelines, while more aligned with the IRS, still differ in a few ways. Most importantly, the Attorney General expects greater levels of detail on individual community benefit programs and community needs (9).

Table 1

| Create and make public a Community Benefits Mission Statement |

| Demonstrate commitment to the Community Benefit Implementation Strategy at the highest levels of the organization |

| Embed community engagement into each step of the Community Benefit process paying particular attention to diverse perspectives |

| Conduct a Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) to assess unmet needs in the community, including a focus on social and environmental conditions |

| Include the target populations for discrete programs in the implementation report and include measurable short and long-term goals for each program |

| Report to the Attorney General annually including the CHNA, implementation strategy, self-assessment, full program with goals, measured outcomes, and expenditures by program |

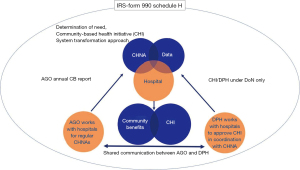

Beyond the new Attorney General guidelines, some nonprofit hospitals in Massachusetts may need to comply with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH) Determination of Need (DoN) regulations and, if located within the City of Boston, the City’s payment in lieu of taxes program (see Figure 1 for a diagrammatic representation of these policies) (30). The Determination of need process mandates that 5% of all hospital expansion spending be set aside for community-based health initiatives, including both public health and social determinants of health (30). Determination of need activities only apply to those hospitals undertaking construction or expansion projects. Per the Massachusetts Department of Public Health’s website, the objective of the Determination of Need program is “to encourage competition with a public health focus; to promote population health; to support the development of innovative health delivery methods and population health strategies within the health care delivery system; and to ensure that resources will be made reasonably and equitably available to every person within the Commonwealth at the lowest reasonable aggregate cost” (31). While the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and payment in lieu of tax policies are not specific to community benefit spending as defined by the IRS or Attorney General, nonprofit hospitals are still required to manage these additional regulatory processes and report accordingly.

Most hospitals presumably designate one or more individuals to manage hospital activities focused on community needs, specifically focusing on performing the required community health needs assessment and operationalizing any programs from the documented implementation strategy. Survey data has shown significant heterogeneity in hospital community benefit department make-up and structure; however, qualitative data on how community benefit administrators (CBA) make sense of their role within the organization and how they manage changing expectations have been limited (32).

Methods

Study design

We utilized semi-structured interviews to collect qualitative data. We employed thematic analysis as a guide for our research. Thematic analysis is a flexible qualitative research method used to gain insight into rich, often complex sets of data (33).

Sample selection

As of 2017, Massachusetts was home to 62 acute care hospitals, of which 52 (84%) were operated as nonprofit corporations and were thus subject to federal community benefit regulations and state guidelines (34). We drew from these hospitals for this pilot study. We sought to assemble a diverse sample by including hospitals in urban and nonurban locations as well as hospitals in the eastern, central, and western parts of the Commonwealth to account for regional variation.

During recruitment of this convenience sample, we requested through unsolicited email or phone calls the participation of 24 individuals identified as community benefit leaders within Massachusetts hospitals (identified through online search methods). Sixteen requests went unanswered, and two individuals declined to participate. We also asked current participants to introduce us to community benefit leaders at other hospitals, thus utilizing a snowball sampling method. The final sample included nine nonprofit hospitals and one for-profit hospital in Massachusetts. While for-profit hospitals are not subject to IRS regulations or Attorney General guidelines, many voluntarily comply.

To assess the representativeness of our participant hospitals to all Massachusetts hospitals, we obtained characteristic of hospitals (e.g., number of staffed beds and gross patient revenue) from a publicly available state database (34). Based on this comparison, the participant hospitals were somewhat larger and reported higher gross patient revenue. Table 2 presents an overview of participant hospitals (35).

Table 2

| Size | Teaching | System or independent | Predominantly underserved population | Hired consultants for CHNA (2013 or 2016)? |

Total community benefit spending as % total expenses* | Financial Assistance and Means-Tested Government Programs as % total expense* | Community health improvement services and community benefit operations as % total expense* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large | Yes | Independent | Yes | Yes | 20–25% | 5–20% | 0.5–1% |

| Medium | No | System | Yes | Yes | 2–5% | 0–5% | 0–0.5% |

| Large | Yes | System | No | No | 5–10% | 0–5% | 0–0.5% |

| Small | No | System | No | Yes | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Large | Yes | System | No | Yes | 10–15% | 0–5% | 0.5–1% |

| Small | No | System | Yes | Yes | 5–10% | 5–10% | 0–0.5% |

| Large | Yes | System | No | No-CHIP | 5–10% | 0–5% | 0–0.5% |

| Large | Yes | Independent | No | Yes | 10–15% | 5–10% | 0–0.5% |

| Medium | No | System | Yes | Academic partner | 0–5% | 0–5% | 0–0.5% |

| Large | Yes | System | No | Yes | 5–10% | 0–5% | 0–0.5% |

*, form 990 Schedule H, last year available on Propublica.org, range provided. Ranges are provided to protect the identify of participating hospitals. Hospital D is part of a for-profit health system so Form 990, Schedule H is not required. Hospital size: small =1–199 staffed beds, medium =200–399 staffed beds, large =400+ staffed beds. CHIP, community health improvement plan; CHNA, community health needs assessment.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northeastern University (IRB# 17-10-26) and informed consent was taken from all participants.

Recruitment began in December 2017 and continued until August 2018. Our data was collected during the Attorney General guideline update process, before and after the guidelines were finalized but prior to the first year of reporting in 2019.

Data collection

We conducted interviews with thirteen community benefit administrators from the 10 hospitals/hospital systems included in the study sample. Six semi-structured interviews with community benefit administrators were performed one-on-one and in-person at the individual’s office (located in or near the hospital). One interview was performed via telephone due to scheduling challenges. Three interviews included two individuals from a single hospital, a junior community benefit administrator and a senior community benefit administrator.

Interviews were conducted using an IRB approved interview guide (see Appendix 1). All interviews were voice recorded using the Apple iPhone Voice Memo application. Transcription was performed by a third party and quality checked by the first author.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed according to methods outlined by Braun and Clarke (Thematic Analysis, 2006). All interviews were transcribed then uploaded to Atlas.ti v.8 for coding (33). We followed an inductive and iterative approach to data analysis.

The primary author coded all 10 transcripts. The most frequently identified codes are defined and summarized in Table 3. Codes were then aggregated into preliminary themes. Pre-themes and associated supporting evidence (fully coded transcripts and codebook) were reviewed by a second member of the research group for final theme development. An external research consultant performed a reliability and validity assessment by coding five deidentified transcripts using the same codebook. The inter-rater reliability for coding was greater than 95%. Themes were found to be grounded in the data.

Table 3

| Code | Definitions/Notes | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Challenge | Difficulty or problem in an aspect of community benefit operations; something to be overcome | 71 |

| Cross-sector collaboration | Participation on community benefit tasks from individuals or organizations outside of the health delivery system. Can include public health, education, housing, law enforcement, religious sector, etc. | 52 |

| Finance/money | How hospital allocated funds to CB; cost of programs; grant solicitation; return on investment; high cost of certain patient populations | 46 |

| Attorney general process | Any comment on provisions within or tangential to new Attorney General guidelines | 32 |

| Perception of public health | Experience with: local health departments; Massachusetts State Department of Public Health; public health researchers/academia | 28 |

| Resource constraint | Desire to perform more but unable to because of not enough staff, money, time, etc. | 26 |

| Data | Discrete elements of information that are captured and recorded | 25 |

| Working with other hospitals | Issues of collaboration and competition in planning or executing community benefits | 23 |

| Social determinants | The conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship and age that affect a wide range of physical and mental health outcomes | 23 |

| Determination of need | A specific type of CB investment run by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health for capital expenditures by hospitals. Dollars from DON have different rules than community benefit regulations under the Attorney General or Affordable Care Act | 21 |

| Regulatory agencies | General term for Federal Gov’t (especially Internal Revenue Service), Massachusetts Attorney General and Massachusetts Department of Public Health | 20 |

| Measure | Type of data- ability to define a set of data and use to make decisions | 19 |

| Decision making | The act of weighing positives and negatives about what is known to affect change; often involves multiple stakeholders | 19 |

| Sustainability | The ability for a program to continue operations without the need for continued hospital CB funding | 17 |

| Initiative example | An action taken by a hospital as part of their strategic implementation of community benefits from the community health needs assessment | 17 |

| Role | The job or expertise associated with community benefits; could be at the individual, organizational or governmental level | 17 |

| Perceptions of the ACA regulation | Any comment on provisions within or tangential to community benefits under the ACA (including IRS provisions to operationalize) | 17 |

| Frustration | Perception of something not working well and causing anxiety/disillusionment | 17 |

| Accountable Care Organization | Groups of doctors, hospitals or other health care providers who voluntarily coordinate to provide high quality care. Accountable Care Organization ties provider reimbursement to quality metrics and reductions in cost of care. | 16 |

Codes used less than 15 times are not included.

Results

CBA characteristics and hospital organizational structure

Our first research aim was to gain some insight to CBA characteristics and the organizational structure of community benefit departments within hospitals. We found that individual CBA backgrounds as well as community benefit departments’ size, leadership structure and funding varied considerably (see Tables 4,5). The length of time in the role of community benefit administrator ranged from less than a year (20%) to greater than 10 years (30%). Many CBAs acknowledged “falling into” their work rather than purposefully seeking out the role. Some CBAs stated that they were promoted into their jobs from within the hospital or were brought into the hospital from a community organization that interfaced with the hospital. Other CBAs were clinicians (MD/RNs) who found community benefit management to be a nice blend of their clinical training and public health passion.

Table 4

| Title | Years in role | Status |

|---|---|---|

| Director Foundation Relations, Government Grants and Community Benefits | 6 | Part-time |

| Director of Community Relations | 10 | Full-time |

| Director of Reporting and Compliance | 17 | Full-time |

| Director of Mission and Community Partnership | <1 | Full-time |

| Director of Community Benefits | 6 | Full-time |

| Vice President of Care Continuum | 5 | Part-time |

| Community Relations/Community Health Manager | 7 | Full-time |

| Executive Director of Community Health | 4 | Full-time |

| Director of Community Benefits | <1 | Full-time |

| Manager, Community Relations and Community Benefit | 13 | Full-time |

Table 5

| Reporting structure | # Full time equivalents | Operating budget |

|---|---|---|

| Development Officer | 1–2 | No |

| Vice President of Administration | 3–5 | Yes |

| Unavailable | 3–5 | Yes |

| President | <1 | Yes |

| Senior Vice President Corporate and Community Affairs | 1–2 | Yes |

| Chief Administrative Officer | 1–2 | No |

| Vice President of Community Relations | 10+ | Yes |

| Senior Vice President for Network Development and Strategic Partnerships | 5–10 | Yes |

| Director of Government and Community Relations | <1 | Yes |

| Vice President for Government and Community | 1–2 | Yes |

Despite the varied entry into the CBA role, some CBAs identified lack of direct training as an issue they faced. Additionally, one interviewee brought up the concern of succession planning: “what would the hospital do if I left, I have so much knowledge and nobody taught me.”

All but two hospitals had full-time community benefit administrators. Those who reported being part-time worked for the hospital full-time but had other roles that were an equivalent or greater part of their overall responsibilities. As stated earlier, there was no consistency in reporting structure for CBAs across their respective hospitals (Table 4,5).

The size of the hospital community benefit department also varied. Six hospitals had fewer than two community benefit staff members (60%), two hospitals had 3–5 staff members (20%), one hospital had 5–10 staff members (10%), and one hospital had more than 10 staff members (10%). While the largest community benefit department was at a large hospital, another large hospital did not have a community benefit department at all, rather assigning oversight to an individual situated in an associated department. Also, by comparison, the only for-profit hospital in our sample (amongst the smallest by number of beds) had a single full-time CBA. Therefore, the size of the community benefit department did not track uniformly with size of the hospital.

All but two community benefit administrators stated that their department received a distinct operating budget to cover salaries, consultant fees for required work, and grant-making to community organizations. The two hospitals that did not have an operating budget were those that did not have a full-time staff member. While we did not ask interviewees to disclose or discuss specific budget amounts, many CBAs alluded to budget concerns during the interviews.

The responses from the only for-profit community benefit administrator did not differ in content or pattern to the responses from the nine nonprofit community benefit administrators.

Challenges

We were interested in learning about the challenges that CBAs faced in performing their day-to-day work. Three main themes emerged: (I) data challenges, (II) evaluation challenges, and (III) resource constraints including sustainable funding.

Data challenges

Lack of real time, high quality data was a major concern for all CBAs. Many CBAs reported relying on public health agencies, academic partners, or consultants to provide them with community-level health data, especially during the community health needs assessment process. A lack of data consistency increased the burden for CBAs to justify why certain health needs were being prioritized.

So, if you’re trying to work in a particular neighborhood... you have to sort of go through and pick out what’s happening in each neighborhood. Or sometimes it is geographical, but it’s not tracked year over year. One year it might be colon cancer that’s the focus [of public health] and then the next year, colon cancer isn’t even mentioned.

Additionally, many hospitals struggled with the lag time even when data were available. As one administrator stated: “The data is 18 months to two years old. At best.”

One of our biggest struggles is data. So, we’re really good at knowing what’s happening when people come into our hospitals. I understand population data can’t be real time... but if we can look at our internal data and we can understand what’s happening with people who are at least coming into our system, and that is reflective, to a degree, of some large swaths of the population and then we compare that to the best that we’re getting out of the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, which is like two years old. It’s incredibly hard to get people to make decisions based on data that are that old.

Evaluation challenges

CBAs expressed challenges in assessing the impacts of community benefit programming. Program evaluation was mentioned in two contexts: (I) a lack of direct program data, and (II) insufficient skills and resources to analyze the data when it was available. CBAs stated that many of the programs they implemented had no discrete health “outcomes”. The challenge of collecting data on individuals who did not seek care at their facility was cited as one reason why process measures, such as numbers of individuals served, were most frequently reported.

We have data on events and activities. We don’t have data that indicates a change [in behavior or outcomes].

Not all community benefit programs lacked such evidence, however. Programs that could demonstrate direct hospital related outcomes, such as the number of emergency room visits, did report health outcomes. These programs tended to be long-term (in place for 5+ years), were clinical in nature versus social (aimed at issues of race, public safety or economic) or behavioral (i.e., smoking or drinking) and included a financial outcome for the hospital (quality measures/pay-for-performance). One hospital described measurement in their current community benefit plan.

So, we’ve been able to track data, do our calculations, publish papers for the community asthma initiative. We’ve got good data. On the other hand, our behavioral health program in schools where we’re providing both direct services as well as a lot of training and consultation for teachers, we have much less data. We have things that we track but it’s much more qualitative. We also have another program that focuses on kids who have learning disorders and ADHD. Again, we’ve got numbers served, satisfaction, and those kinds of things. But not as much in terms of any hard and fast data.

The lack of formal evaluation support and training was also a concern cited by some CBAs.

We don’t have the resources to do that. So, I’ve been looking at—for lack of a better word—courses, I guess. Or some kind of education so I can familiarize myself with the terminology more.

Only one CBA reported having a full-time evaluation expert on staff within the community benefits department. Several CBAs reported that due to limited resources for program evaluation, they focused on program offerings with process measures that were more manageable for reporting (e.g., educational events, health fairs, volunteer time, etc.) (36).

Resource constraints and sustainable funding

In a rapidly changing payment and market environment, hospitals are constantly re-assessing capital and operating budget allocations. Hospital leaders make investments to improve the hospital’s bottom line—either in securing new patients, increasing reimbursements, decreasing operating costs or decreasing financial risk (37).

The amount and sustainability of funding allocated to support external community benefit programs was a source of concern and frustration. One CBA stated that they were hoping the 2018 Attorney General guidelines would have included a minimum spending threshold (e.g., percentage of operating expenditures) for community benefits to help address the ongoing lack of funding from hospital leadership.

I was kind of hoping and holding my breath that from the Attorney General guidelines that there would be some nugget there around a budget. I’ve been trying to plant softly, and I think it comes from some of our conversations around how year to year hospital finances are challenging. They’re going to continue to be challenging... But with that said, community benefits cannot go away. It’s not going away... we are still a charitable not-for-profit, and we have an obligation. So, no matter what our financial status, we still need to make some type of commitment and obligation. I think it would [show] an authentic commitment to the community.

A few CBAs stated they encourage external partners to seek grant funding to enable sustainable operations for their organizations after the community benefit commitments expire. CBAs highlighted that while some programs receive multi-year funding, many receive one-time allocations, thus encouraging recipient organizations to work with grant writers as part of their overall strategy to improve community benefits beyond their direct financial commitment. One CBA described seeking external grant funding to help with internal community benefit operations at their small hospital.

We also have used some DoN money to fund a community grant writer. So, any of our grantees that we do fund, we connect them with the grant writer to also be looking at how they can be prospecting for other resources.

Another CBA commented:

So, I’m actually applying for a Foundation Award to see if they will cover staffing. Somebody to help me. At least for this year. And then maybe keep it going after that. But I don’t know if that will come through.

How CBAs see their role

We were interested in understanding how CBAs conceptualize their role within the context of hospitals’ provision of community benefits. Two predominant perspectives emerged: swimming upstream and hope and fear for future community benefits.

Swimming upstream

CBAs reported feeling a certain sense of ambiguity about both the meaning and purpose of community benefits and, as a result, their own roles, and responsibilities. Community benefit administrators felt that it was difficult to share the valuable work they were doing with constituents inside and outside of the hospital. Regulatory requirements with different definitions of community benefits (IRS vs. Attorney General; Massachusetts Department of Health Determination of Need vs. Community benefit) made it difficult for CBAs to clearly describe their successes.

During the interviews, we were told that one hospital community benefit board asked their CBA to track how they allocate their time to understand and evaluate the work the community benefits department was performing, rather than focusing on population health improvements the CBA was trying to achieve.

We started tracking—at least my board was asking me recently—just to track even what, you know, where I’m spending the most time. So, I started—because I’m going to go through my calendar and figure out where I was that month. So, I started tracking how much time that we are spending around substance abuse, mental health, etc.

Many hospitals will include expanded screening or community workers into their hospital strategic plans to address documented needs; however, some CBAs expressed disappointment that their work, while prominently grounded in the hospital mission, did not feel aligned with their hospital’s strategic business goals.

Our strategic plan for the organization is not informed by our community health needs assessment.

According to some CBAs, hospital leadership was often not aware that hospital community benefit funding is separate and distinct from determination of need funding. CBAs expressed frustration that hospital senior leaders did not understand the differences and felt that a lack of understanding may be leading to lower funding for community benefit work.

I’ve been trying to advocate even just, first of all, a budget just so we can start from somewhere and continue to grow and build and work with our community benefit advisory councils. The pushback I get is when we have Determination of Need investing, why do we need those community benefit budgets? And I say over and over again, the Department of Public Health has made it very clear that Determination of Need dollars are not to replace or supplant community benefit budget. And I don’t think that that has quite resonated yet with the people here. So, we’re still kind of internally swimming upstream in terms of that.

Another source of frustration was being asked to demonstrate, or at least conceptually defend, a return on investment.

If I’m going to make a pitch then I know that the CFO and the CEO are going to ask me about that, or the value add. It might not be specifically a return on investment, but it will be the value add to us as an organization or to the community.

CBAs stated a recognition that return on investment was a desirable measure to have when assessing hospital investments but also felt frustrated when such evaluations were not possible.

There may never be something that tells you that that community garden has a return on investment. And getting an evaluation for that may in itself cost more than the program money we’re investing.

There’s definitely a strong movement toward return on investment. And I—we have a very cautious effort of having a balance now of programs that …are going to have a return on investment [and those that won’t]. And we might have a small contribution, a couple thousand dollars, to this little elementary school so they can run an afterschool exercise class that we’re not going to [show return on investment]… And we have things like asthma where we have positive outcomes. We are doing the evaluation now and having formal studies done to show, in fact, the return on investment. And that takes some time. And that’s the other challenge, too.

The financial aspects of community benefit investments extended beyond return on investment to include changes in reimbursement under value-based health care. CBAs found there was a great deal of overlap and confusion between the goals of community benefits and the goals of the population health management department, i.e., those managing costs and outcomes in Medicaid Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs).

The term population health didn’t exist eight years ago. Population health management, which is different than population health, is where they’re focused. But they often shorten it to population health then nobody knows what anybody’s talking about anymore. I see people using community health and population health interchangeably, but we need to be careful. So, when people start talking about population health—I say “okay, wait a minute, what is the focus?”

CBAs stated that community benefit programming should be aimed at helping “financially at risk” patients but also go beyond those who receive care at their hospital. We learned from the interviews that one large hospital system moved its community benefit department to be co-located with the population health management/Medicaid ACO program to address social determinants of health.

So, …the ACO business model around the provision of care related to population health really has made a lot of connection points with community health.

Hopes and fears about guideline impact

CBAs were both hopeful and trepidatious that reporting changes, mostly stemming from the new Massachusetts Attorney General’s guidelines, would improve community benefit department operations and community health overall.

The most cited concern was meeting the Attorney General’s increased expectations for community benefit reporting. These concerns centered around three areas: ability to impact large-scale social determinants (“do they really expect hospitals to fix all social needs?”), reporting long-term outcomes when they have little confidence that this can be achieved, and meeting the new expectations for community engagement and self-assessment.

Most CBAs said the Attorney General’s emphasis on the social determinants of health was a positive change. However, they indicated that showing improvements in social determinants would be a challenge and would likely require large sums of money and lengthy time horizons that they didn’t feel was possible. Most of the CBAs we interviewed seemed willing to shift focus towards impacting the social determinants of health but highlighted the transition could negatively impact local community groups.

You can’t forget the direct programs and services too because when you go to communities and say we’re just going to focus on one area... That’s really disheartening for communities.

While most CBAs agreed that hospitals should focus on the social determinants of health, they also felt the Attorney General’s expectations may be too high for a hospital.

You might find [from your needs assessment] that transportation is the main issue, highest data points. But then you say, okay, we’re a hospital. We cannot buy a city bus system.

Not only were there apprehensions about the scope of the problems that hospitals were being asked to address, but there were also concerns about being able to adequately show progress given limited staff and available data. Ultimately, the CBAs were concerned about being judged for “slacking” and putting their hospital at risk when they felt they were doing the best they could.

I can tell you how many people attended, how many people were screened, what happened when they screened positive, whether they got treatment. I can tell you all of that but to really know whether my, you know, my corner store initiative for food access is really having an impact... Are they eating greens and is that changing BMI, right? That takes years and data. So, the thing is that to have the quantitative data, to be able to track incident rates of certain things. And in particular, to track social determinants of health because that’s really what we’re trying to address... And so, we’re seeking a way, really, to get more validated data on an ongoing basis so that we could respond to the needs in a community that are not specific to a disease trajectory, but are related to health with a capital H. And that’s been the goal but it’s been going on almost five years now and we haven’t been able to get it.

There were also concerns about the increased reporting requirements causing unnecessary burden on already stretched community benefits departments.

So then, now I’ve got a Determination of Need process, I’ve got the Attorney General process, I’ve got the schedule H (IRS), and I’ve got the payment in lieu of taxes. So, what’s going to happen is ultimately, we’re just going to be doing less.

When I look at all of the forms... What’s going to happen is, opposed to me being out in the community, I’m going to be sitting in my office doing forms.

Several of the more experienced CBAs identified strategies that might improve the community benefits process overall. The concept of anchor institutions was raised by several CBAs as a means to locate community benefits within hospital operations and overcome sustainability concerns. An anchor institution is defined as a placed-based entity, often a nonprofit institution, that is tied to their surroundings (their local communities) by mission, invested capital, or relationships to customers, employees, and vendors (38). There is ongoing research on the impact such institutions make on the health and wealth of their communities (39,40). One CBA hypothesized the future of anchor institutions and community benefits:

Community benefits, I’ve always described as the tail wagging the dog. It’s really operational resources. The power of the organization is in our purchasing, it’s in our hiring, it’s in our business, the business that we do. And so, it would be great if community benefits were further transformed such that the hospitals would be credited for operational investments. So that would then mean it’s no longer a battle and those battles are just a different battle. So, the hiring strategy as well. The hospitals would love to make more investment in hiring... It would make sense for them to invest in community-decreed job hiring pathways, career pathways, because it’s good business, but it’s also a hell of an investment for the community. So, you can think about place-based investing.

Another idea CBAs raised for managing community benefit operations was the concept of a community innovation fund. An innovation fund is an account where an initial investment is made by a hospital that can then solicit funding from outside organizations, including the business sector, to tackle upstream social determinants of health that healthcare providers would not likely invest in independently.

Discussion

In the US, there have been long-standing societal and legal expectations that nonprofit hospitals provide community benefits in return for their tax-exempt status. Massachusetts, like many states, has been seeking to improve hospitals’ contributions to the wellbeing of their communities. With its recently revised Attorney General guidelines aimed at improving the effectiveness of community benefits programs, Massachusetts offered an excellent opportunity for a pilot study of the operational and implementation issues that hospitals face with respect to their community benefit programs. This research sought to provide insight into three current gaps in the community benefit literature: the nature of hospital organizational structures for community benefit departments, challenges that CBAs face when implementing changing regulations, and how CBAs see their role in the context of hospitals’ provision of community benefits. While data exist on hospital structures and CBA challenges in the form of surveys, there has been limited academic inquiry of the underlying phenomenon.

While most of the CBAs interviewed expressed hope that “their hospitals would get there”, in terms of developing a strong community benefits program, they also expressed frustration with the expectations, uncertainty, and misperceptions that they believed changing community benefit policies created for hospitals. Some CBAs noted a discrepancy between external expectations for nonprofit hospitals to focus on social determinants of health and the lack of internal financial commitment by their hospitals. CBAs also lamented the lack of data to measure the impacts from investments beyond the hospital walls. While this finding appeared somewhat more pronounced among CBAs representing small hospitals, we also heard similar concerns among some of the CBA of the larger hospitals as well. Our finding regarding the challenges CBAs face for conducting outcome measure evaluation is in line with other published research (36).

Some additional themes emerged during the interviews regarding opportunities for hospitals to provide community benefits. Nonprofit hospitals as anchor institutions to focus community health improvement was discussed. The benefit of having hospitals as anchor institutions to a community has been described extensively, and thus was not a novel concept (41,42). The creation of an innovation fund with the intent to grow hospital community benefit dollars through the solicitation of external funding was another idea raised during the interviews. This may hold promise for impacting social determinants of health and is similar to investment programs described by other institutions (42). However, this concept brings up many potential concerns, namely who would have ultimate accountability of these funds, who would determine how the money is spent, does each hospital have their own fund and what oversight mechanisms would be put in place?

Moreover, the desire for hospitals to better manage the overall health of their population is an evolving issue in health care reform, so the overlap between community benefits and population health management may be natural and expected. This phenomenon was brought up during the interviews and has been discussed in other articles (36). It may help a hospital financially if the community benefits department is focusing on those needs for which the hospital also has financial liability. However, population health management is a narrow and specific use of what is intended to be a broader community health improvement benefit.

All of the CBAs we interviewed expressed support for the updated Massachusetts Attorney General guidelines in principle, especially regarding improved alignment between the IRS and Massachusetts Department of Public Health reporting and expectations. However, perceived difficulties (or the associated fear of difficulties) in meeting the Attorney General expectations were a common concern. This sentiment was conveyed by CBAs as a source of frustration as well as an opportunity. At the same time, although community benefit guidelines have been in effect in Massachusetts since the mid-1990s, there has been little formal evaluation showing that the guidelines have contributed to an overall improvement in the health of communities (6,29,43). The updated Attorney General guidelines are intended to encourage hospitals to more concretely measure population-level health outcomes stemming from their community benefit investments.

Tools and best practices for nonprofit hospital community benefit activities do exist. Organizations such as the Catholic Health Association, the Center for Community Investment and Community Catalyst have resources available for hospitals and health systems seeking to improve their community benefit programs (44-46). Similarly, public health organizations such as the Center for Disease Control and the National Association of County and City Health Officers (NACCHO) offer ways in which nonprofit hospitals can partner with public health groups to maximize impacts from community benefit programs.

Although the CBAs we interviewed were concerned about their ability to meet community benefit expectations, they expressed a sense of optimism that positive impacts will come over time even though it may be challenging. As one CBA stated, “We’re building the road as we travel on it.”

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size was small, with only 10 hospitals/health systems and 13 individual CBAs participating. Using purposive sampling and the snowball method led to oversampling CBAs at hospitals with more staffed beds and higher gross patient revenues. Thus, perceptions from those who participated in our study may not be representative of all CBAs within nonprofit hospitals in Massachusetts.

Second, Massachusetts hospitals are most likely not representative of hospitals nationally. Important differences may exist for two distinct reasons. Massachusetts has a longer history of community benefit oversight than other states so Massachusetts CBAs may be more accustomed to regulatory changes. Additionally, Massachusetts residents tend to be better insured than residents in other states. As with community benefit regulations, Massachusetts was the first state to implement health care reform with an effort to provide health insurance coverage to all residents. It may be expected that an insured population would lead to lower charity care expenditures by hospitals. Thus, hospitals in Massachusetts may have more financial resources to allocate to community benefit programming.

Finally, this study only focused on the perceptions of hospital CBAs and not on other stakeholders involved in improving community health. The perceptions of public health department professionals, government regulators, community organizations and community residents would also be necessary to provide insight on nonprofit hospital community benefit effectiveness.

Implications for policy makers

A key policy implication from our study is the need to clarify expectations for nonprofit hospitals regarding their provision of community benefits. No consensus exists on what policy makers or community stakeholders want from nonprofit hospitals in return for tax exemptions. Moreover, differences exist between state and federal guidance for community benefits. Without a comprehensive, aligned set of expectations, many hospitals may try to appear to be as responsive to their community as possible while avoiding making meaningful financial commitments for community benefits. A 2020 audit of community benefit programs and outcomes in Montana found that community benefit spending by Montana hospitals had no clear benefit for the citizens of Montana (47).

Policy makers should consider reforms in federal, state, and local oversight of nonprofit hospitals’ provision of community benefit. However, even if policy makers create more clearly defined expectations, additional policy changes may still be needed to ensure nonprofit hospitals make necessary investments. For example, although the Massachusetts Attorney General expects hospitals to focus on social determinants of health, these need to be contextualized in terms of other public and private policy improvements. The amount of funding and length of time necessary to achieve improvement on the social determinants of health are difficult for hospitals who operate on annual budgets and are reimbursed per acute care episode. There are ongoing efforts from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and similar organizations to create a coherent set of expectations for hospitals to invest in the social determinants of health (46-48). The output of these efforts is greatly needed.

Enforcement of community benefit regulations must also have teeth. Without a meaningful deterrent to improper behavior, hospitals may not live up to social and regulatory expectations. Currently, the federal community benefit rules include an excise tax penalty for hospitals that fail to meet reporting requirements ($50,000) (49). Additionally, if a hospital does not comply with the broader requirements under Section 501(r) (financial assistance policies, community health needs assessment, etc.), the IRS has the ability to withdraw tax-exempt status (49). However, a $50,000 fine may not be sufficient to ensure hospitals meaningfully invest in community health outside their walls, particularly for highly profitable hospitals. To date, very few nonprofit hospitals have been fined or had their tax-exempt status revoked (9,50).

Conclusions

Nonprofit hospitals have come under increased scrutiny for inadequate provision of community benefits. Federal and state policy makers have responded through guidelines and regulations designed to enhance transparency and accountability among hospitals regarding the provision of such benefits. Yet, these efforts form a somewhat confusing and, in some instances, conflicting set of requirements that may not be achieving their intended effects. Indeed, a recent IRS report to Congress (May 2018) shows decreased spending by private, tax-exempt hospitals on “community health improvement services and community benefit operations” (decrease of 9% between 2011 and 2014) (8). Our study sought to “look behind the curtain” of nonprofit hospital community benefit departments and try to understand the day-to-day experience of community benefit administrators. Given the limited scope of our study, more research is needed with a larger sample of national hospitals to better understand the organizational behaviors driving hospital community benefits overall. However, clear expectations, increased oversight, and stronger enforcement may be needed to ensure expected societal benefit from these charitable organizations. Such changes should be considered at both the state and federal level.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Ralitsa Todorova for her support with qualitative methods.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-21-44/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jhmhp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jhmhp-21-44/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northeastern University (IRB# 17-10-26) and informed consent was taken from all participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rosenbaum S, Kindig DA, Bao J, et al. The Value Of The Nonprofit Hospital Tax Exemption Was $24.6 Billion In 2011. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34:1225-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torio CM, Andrews RM. National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011: Statistical Brief #160. 2013 Aug. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006.

- Singh SR, Cramer GR, Young GJ. The Magnitude of a Community's Health Needs and Nonprofit Hospitals' Progress in Meeting Those Needs: Are We Faced With a Paradox? Public Health Rep 2018;133:75-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Young GJ, Flaherty S, Zepeda ED, et al. Community Benefit Spending By Tax-Exempt Hospitals Changed Little After ACA. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37:121-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sullivan HR. Hospitals' Obligations to Address Social Determinants of Health. AMA J Ethics 2019;21:E248-258. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eckstein E, Hattis PA. Hospitals Investing in Health: Community Benefit in Massachusetts. Health Catalyst; October 2016.

- Koskinen JA. Report to Congress on Private Tax-Exempt, Taxable and Government-Owned Hospitals. Internal Revenue Service; January 2016.

- United States Government. Report to Congress on Private Tax-Exempt, Taxable and Government-Owned Hospitals. Internal Revenue Service; May 2018.

- Massachusetts Office of Attorney General Maura Healey. The Attorney General's Community Benefits Guidelines for Non-Profit Hospitals. February 2018.

- Lopez L 3rd, Dhodapkar M, Gross CP. US Nonprofit Hospitals' Community Health Needs Assessments and Implementation Strategies in the Era of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2122237. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnett K. Supporting Alignment and Accountability in Community Health Improvement: The Development and Piloting of a Regional Data-Sharing System. Public Health Institute; April 2014. Available online: https://www.phi.org/thought-leadership/supporting-alignment-and-accountability-in-community-health-improvement-the-development-and-piloting-of-a-regional-data-sharing-system/

- Barnett K, Somerville MH. Schedule H and Hospital Community Benefit—Opportunities and Challenges for the States. Baltimore, MD: The Hilltop Institute, 2012.

- Institute of Healthcare Advancement. Results of a National Salary Survey of Community Benefit Professionals. Available online: https://www.communitybenefitconnect.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Community-Benefit-Connect-Salary-Survey-Report-Final.pdf

- HCUPnet. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/index.html

- Ivancevich JM, Matteson MT, Konopaske R. Organizational behavior and management. 10th ed. New York, NY.: McGraw-Hill Irwin; 1990.

- Pfeffer J. Understanding Power in Organizations. California Management Review 1992;34:29-50. [Crossref]

- United States Government. Revenue Rule 56-185, 1956-1 C.B. 202. 1956.

- Colombo JD. The failure of community benefit. Health Matrix 2005;15:29-65. [PubMed]

- United States Government. Revenue Rule 69-545, 1969-2 C.B 117. 1969.

- Government. US. Instructions for Schedule H (Form 990). In: Service IR, editor. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-schedule-h-form-990; IRS; 2014.

- United States Government. An Act Entitled The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In: Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Obama Care Act: Washington, D.C. : U.S. G.P.O.; 2010.

- United States Government. Requirements for 501(c)(3) Hospitals Under the Affordable Care Act – Section 501(r). In: Internal Revenue Service; Updated 20-Sept-2019.

- Cramer GR, Singh SR, Flaherty S, et al. The Progress of US Hospitals in Addressing Community Health Needs. Am J Public Health 2017;107:255-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pennel CL, McLeroy KR, Burdine JN, et al. Nonprofit hospitals' approach to community health needs assessment. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e103-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beatty KE, Wilson KD, Ciecior A, et al. Collaboration among Missouri nonprofit hospitals and local health departments: content analysis of community health needs assessments. Am J Public Health 2015;105:S337-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rozier MD, Singh SR. Nonprofit Hospitals' Process for Community Health Improvement: A Qualitative Study of Leading Practices and Missing Links. Popul Health Manag 2020;23:194-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hilltop Institute. State Community Benefit Requirements and Tax Exemptions for Nonprofit Hospitals 2016. Available online: https://hilltopinstitute.org/our-work/hospital-community-benefit/hcbp-state-comparison/

- Niewenhous MD. Massachusetts Determination of Need Program Proposes Regulatory Revisions Mintz.com2018. Available online: https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2146/2018-09-massachusetts-determination-need-program-proposes

- Hattis P, Eckstein E. Tracking hospital community investments. CommonWealth 2018;

-

Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Determination of Need Community-Based Health Initiative Planning Guideline, January 2017 . Available online: https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2017/01/vr/guidelines-communityengagement.pdf - Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Determination of Need (DoN) 2021. Available online: https://www.mass.gov/determination-of-need-don

- Connect CB. Results of a National Salary Survey of Community Benefit Professionals. Institute for Healthcare Advancement; 2018.

- Todd NJ, Jones SH, Lobban FA. "Recovery" in bipolar disorder: how can service users be supported through a self-management intervention? A qualitative focus group study. J Ment Health 2012;21:114-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Center for Health Information and Analysis (CHIA). Hospital Profiles. Available online: http://www.chiamass.gov/hospital-profiles/; December 2018.

- Schwencke K, Tigas M, Wei S, et al. Nonprofit Explorer. ProPublica; Updated Sep 15, 2021.

- Rozier M, Goold S, Singh S. How Should Nonprofit Hospitals' Community Benefit Be More Responsive to Health Disparities? AMA J Ethics 2019;21:E273-280. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ly DP, Cutler DM. Factors of U.S. Hospitals Associated with Improved Profit Margins: An Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:1020-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dubb S, McKinley S, Ted H. The Anchor Dashboard: Aligning Institutional Practice to Meet Low-Income Community Needs. College Park, MD: The Democracy Collaborative at the University of Maryland, 2013.

- Overiview: Anchor Institutions: The Democracy Project. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/strategies/panel/anchors/index.html

- Cronin CE, Franz B, Choyke K, et al. For-profit hospitals have a unique opportunity to serve as anchor institutions in the U.S. Prev Med Rep 2021;22:101372. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rozier M, Goold S, Singh S. How Should Nonprofit Hospitals' Community Benefit Be More Responsive to Health Disparities? AMA J Ethics 2019;21:E273-280. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oostra R, Zuckerman D, Parker K. Embracing an Anchor Mission: ProMedica’s All-In Strategy. Toledo, OH and Washington, DC: ProMedica and The Democracy Collaborative; May 2018.

- Ndugga N. The Incidental Economist. Frakt AB, editor. WordPress2019. [cited 2019 December 10, 2019]. Available online: https://theincidentaleconomist.com/wordpress/non-profit-hospital-successful/

-

Community Benefit Overview 2020 . Available online: https://www.chausa.org/communitybenefit/community-benefit - The Center for Community Investment. Investing in Community Health: A Toolkit for Hospitals. 2020. Available online: https://centerforcommunityinvestment.org/community-health-toolkit

- Community Catalyst. Community Benefit and Community Engagement 2020. Available online: https://www.communitycatalyst.org/initiatives-and-issues/issues/community-benefit-and-community-engagement

- Montana Legislative Audit Division. Community Benefit and Charity Care Obligations at Montana Nonprofit Hospitals. Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services; September 2020.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Funding Opportunities 2020. Available online: https://www.rwjf.org/en/how-we-work/grants-explorer/funding-opportunities.html?cid=xps_other_pd_ini%3Afundingopportunitiesgoogle_dte%3A20200124

- United States Government. Section 4959 Excise Tax for Failure to Meet the Requirements of Section 501(r)(3) and Noncompliant Facility Income Tax for Failure to Meet the Requirements of Section 501(r). Internal Revenue Service; 2019.

- Atkeson A, Higgins E. How States Can Hold Hopsitals Accountable for their Community Benefit Expenditures. National Academy for State Health Policy; March 15, 2021.

Cite this article as: Cramer GR, McGuire J, Singh S, Young GJ. Hospitals and community benefit requirements: perspectives of community benefit administrators in Massachusetts. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2022;6:16.