Development of mental health alliances in China (2017 Edition)

Chapter one: policies and practices of medical alliances in the health sector in China

Section 1: policy interpretation

Development of policies, rules, and regulations on medical alliances

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 2012, with the implementation of the “Healthy China” strategy and the deepened reform of the medical and health systems in China, the Chinese people’s health and medical services have been improved substantially. The new round of medical reform has steadily advanced, which shifts the priorities of health care and the allocation of medical resources (including technology and talents in large hospitals) to the grass-root medical institutions. On October 18, 2017, the 19th National Congress of CPC was successfully held in Beijing, during which General Secretary Xi Jinping pointed out in his report that the “the main contradiction in Chinese society has become the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life”. In the health sector, it is reflected in the unbalanced and insufficient development of medical resources in various regions while the patients’ demand for disease treatment is rising.

On March 5, 2017, Premier Li Keqiang pointed out in his Government Work Report that “the pilot projects for the construction of various forms of medical alliances will be launched at full scale, and all the public tertiary hospitals will participate in a consortium and play a leading role.” More than a month later, Premier Li further called for the construction of medical alliance at an executive meeting of the State Council. He pointed out that the construction of the medical alliance should be adapted to local conditions, focusing on removing barriers associated with administrative divisions, financial investment, medical insurance payment, and personnel management. He also proposed four medical alliance models: urban medical alliance, medical community, specialized medical association, and remote medical collaboration.

Since 2000, relevant policies and regulations regarding the cooperation among medical institutions have been released (Table 1).

Table 1

| Document | No. | Stipulations |

|---|---|---|

| Guiding Opinions on the Reform of Urban Health Care System | GB [2000] No. 16 | All kinds of medical cooperative institutions are encouraged to cooperate and merge. Medical cooperative groups can be established jointly |

| Opinions of the CPC Central Committee and State Council on Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health System | ZF [2009] No. 6 | Specialized public health service networks such as disease prevention and control, health education, maternal and child health care, and mental health shall be established and improved; the public health service functions of the medical service systems that are based on the primary health care service network shall be optimized; and public health service systems with clear responsibilities, active information exchange, shared resources, and coordinated interaction shall be established. Thus, the effective ways for integrating public health service resources shall be explored |

| People’s Republic of China Mental Health Law | Order of the President of the People’s Republic of China [2012] No. 62 | This law is formulated for the purpose of developing mental health undertakings, regulating mental health services, and safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of persons with mental disorders |

| Several Opinions of the State Council on Promoting the Development of Health Service Industry | GF [2013] No. 40 | Cities with abundant resources in public hospitals should speed up the pilot reform of the medical institutions run by state-owned enterprises. The State has determined that some regions will carry out pilot reforms of public hospitals. Non-public medical institutions shall be guided to develop at a high level and large scale and shall be encouraged to develop into professional hospital management groups |

| Framework of National Health Service System Planning (2015–2020) | GBF [2015] No. 14 | The medical and health service systems shall be developed in a moderate and orderly manner, with priorities on structural adjustment, system integration, and promotion of equilibrium. An integrated medical and health service system that adapts to the national economy and social development and matches the residents’ health needs shall be established. It should be with complete systems, clear responsibilities and duties, complementary functions, and close cooperation. The linkage and division of labour between upper and lower institutions shall be enhanced, and the service functions of various types of medical and health institutions at all levels shall be integrated. Qualified regions shall be encouraged to promote the rational allocation of medical resources through various means such as cooperation, trusteeship, and reorganization |

| National Mental Health Work Plan (2015–2020) | GBF [2015] No. 44 | Through overall planning and resource integration, the government shall take specific actions to strengthen the regional mental health service system to basically meet the people’s access to mental health services and promote the comprehensive development of mental health |

| The General Office of the State Council Issued A Work Summary of 2015 To Deepen the Reform of Medical and Health Care System and the Work Priorities for 2016 | GBF [2016] No. 26 | A variety of division of labor and collaboration models including medical alliances and counterpart support shall be explored, with an attempt to improve policies and measures for promoting and standardizing the construction of medical alliances in cities and counties.... The functions of secondary and tertiary general hospitals should be clarified, so as to define the capability standards of medical services and promote the triage and management of acute and chronic diseases |

| Guiding Opinions of the National Health and Family Planning Commission on Piloting the Construction of Medical Alliances | GWYF [2016] No. 75 | Construction of medical alliances is an important measure to integrate medical resources in a specific region, promote the sinking of high-quality medical resources, enhance the capacity-building in primary medical institutions, and thus improve the medical service system. It is key step to promote the establishment of a rational and orderly hierarchical health care system. In order to fully implement the “Sanitation and Health Plan during the 13th Five-Year Plan”, “Plan for Deepening the Reform of the Medical and Health Care System during the 13th Five-Year Plan”, “2030 Framework Document of the ‘Healthy China’ Plan,” and “Guiding Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Promoting the Classification and Treatment System”, “Guiding Opinions for Construction”, related to document requirements, guides local governments in strengthening the construction and development of medical associations |

| Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Construction and Development of Medical Alliances | GBF [2017] No. 32 | In 2017, a medical alliance framework is basically established, along with the full launch of all kinds of piloted medical alliances, during which all the public tertiary hospitals shall participate and play a leading role. By 2020, the construction of medical alliances shall be fully implemented, and a relatively sound policy system will be formed |

All the tables and figures of the Blue Book are numbered according to the chapter in which they are located.

Interpretation on the Guiding Opinions of the National Health and Family Planning Commission on Piloting the Construction of Medical Alliances

The Central Committee of the CPC and the State Council have been paying high attention to the development of hierarchical medical system and making aggressive push to build the system as an integral part of the basic healthcare system. Local governments have also made extensive explorations in medical alliance and produced substantial outcomes. Based on a summary of successful experiences in building and operating medical alliances, the General Office of the State Council issued on April 23, 2017 the Guidelines on the Construction and Development of Medical Alliance (GBF [2017] No. 32) to strengthen the construction of medical alliances. The National Health and Family Planning Commission also issued the Guiding Opinions of the National Health and Family Planning Commission on Piloting the Construction of Medical Alliances (GWYF [2016] No. 75) (hereafter referred as the “Guiding Opinions”) on January 23, 2017 to set specific rules on the cooperation among medical alliances.

Background

In recent years’ local governments have implemented the decisions made by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council to develop hierarchical medical system and medical alliance at pilot regions. As of the end of 2016, 205 prefecture-level cities, or more than 60% of all prefecture-level cities, had built medical alliance in various forms, such as urban medical alliance, medical community, specialized medical association, and remote medical collaboration that covers outlying poverty-stricken regions. Based on a comprehensive summary of the successful practices in the pilot region, the Guiding Opinions set the goals and missions for the next stage and craft policy framework and institutional mechanism for the construction of hierarchical medical system.

Definition of medical alliance

Medical alliance is an alliance of different grades and types of medical institutions associated through vertical or horizontal integration of their medical resources. At present, there are four well-established models of medical alliance.

- Urban medical alliance in cities—a typical medical group is led by a tertiary or well-reputed public hospital and joined by community clinics, nursing homes, and rehabilitation centers. These institutions share medical resources and work together under the same roof.

- Medical community in counties—a typical medical alliance of this kind is spearheaded by an excellent county-level hospital and joined by township health centers and village clinics. Under the alliance, the county-level hospital plays a pivotal role in leading local health institutions to build a coordinated and collaborative healthcare system.

- Cross-regional specialized medical association—this kind of alliance is generally backed by special departments at hospitals from different regions, as well as national medical centers, national clinical research centers, and their supporting networks. With cooperation among professional departments as its ties, its primary objective is to provide better therapies for major diseases.

- Web-based remote medical collaboration for patients in poverty-stricken areas—this kind of medical network is mainly developed for remote and underdeveloped regions. Well-established public hospitals are encouraged to provide web-based remote services including diagnosis & treatment, teaching, and training, so as to promote the vertical flow of resources, increase the accessibility of premium medical resources, and increase the overall efficiency of medical services.

Aside from these four models, urban and rural hospitals can also form a medical alliance on the basis of their longstanding relationship as givers and receivers of medical assistance. Under this kind of alliance, a tertiary public hospital can take over management of county-level hospitals by sending management teams and medical specialists to help these hospitals improve management and health services. National and provincial public hospitals can also cooperate with regional medical alliance entities to exercise their respective advantages and conduct coordinated research, technology popularization, and talent training, so as to enhance health care services in a broader region.

Objectives on the push for medical alliance

Construction of medical alliances is an important measure to promote the sinking of high-quality medical resources, enhance the capacity-building in primary medical institutions, and thus improve the medical service system. It is key step to promote the establishment of a hierarchical health care system. The Guiding Opinions outlined two-pronged objectives.

- In the first stage through 2017, the primary objective is to build an institutional framework. Specifically, China will launch pilot programs to build various forms of medical alliance. Tertiary public hospitals should be fully involved in the process and play leading roles. All prefecture-level cities at provinces covered by the comprehensive health care reform should each have at least one well-functioning medical alliance.

- In the second stage through 2020, the core objective is to develop a well-established policy system for medical alliance. Specifically, on the basis of experiences gathered from the pilot programs, China will make full efforts to advance medical alliance and construct a well-established policy system.

Basic principles for building medical alliances

The core objectives of building medical alliances are to bring premium medical resources to grass-root hospitals and enhance their healthcare services. Four principles should be adopted during this process.

- Government should play a dominant role in coordination and planning. The government shall exert its functions in planning, instruction, coordination, supervision, and publicity and select several medical institutions to form an alliance based on the local distribution of medical resources and public demands, with cities and counties as the priorities. Factors including business relations, complementary advantages, two-way choice, sustainable development, and history of medical cooperation should also be taken into consideration.

- Sticking to the nature of public welfare and creating innovative mechanisms. The government is obligated to provide public health services and shall safeguard its nature of public well-being.

- Bringing medical resources to grass-root hospitals and enhancing their abilities in providing better medical services. Tertiary public hospitals have a large amount of premium medical resources, and they can provide technical assistance or talent training programs to help grass-root hospitals.

- The general public should be able to get greater convenience and more benefits from the alliance. With the people’s health as a central task, it is important to achieve the accessibility of uniform health care and increase the capacities of grass-root medical institutions by enhancing the quality management of medical services and integrating the prevention, treatment, and management of chronic diseases. The construction of medical alliances shall be linked with preventive and medical efforts, so as to facilitate the accessibility of medical services, reduce disease loads, and prevent poverty caused by disease or return to poverty due to disease. The alliance is also helpful to expedite the development and upgrade of the health industry and increase the general public’s sense of attainment.

How to build a medical alliance in a scientific way

Building a medical alliance in a scientific way is a fundamental precondition to produce tangible results.

- Adjust policies to suit local conditions. Various factors should be taken into account, such as the geographic locations of medical institutions, their functions and positions, their service capacities and business relations, and their willingness to be partners. Thus, medical alliances should be established at different levels and according to local conditions.

- Build different types of medical alliances. In cities and counties, the medical alliance and medical community should be established mainly by the reform of payment options; hospitals across different provinces can develop a specialized medical association for the treatment of specific diseases; finally, in remote and poor regions, more efforts should go to developing a remote medical collaboration network.

- Hospitals should be permitted to make two-way choice. Medical institutions should make two-way choice to form an alliance on a voluntary basis, and factors including business relations, complementary advantages, sustainable development, and history of medical cooperation should be taken into consideration.

- Private hospitals are encouraged to join. A medical alliance can enlist private hospitals as members, to promote horizontal mobility of premium medical resources and increase the service capacity and efficiency of the entire alliance.

How to develop division of labor & cooperation mechanism within the alliance

Hospitals of different levels and categories shall develop fair and effective division of labor & cooperation mechanism characterized by clear objectives and well-defined rights and responsibilities, to make the medical alliance a community of shared services, responsibilities, economic interests, and management.

- Optimize the management and collaboration mechanism. The constitution of a medical alliance shall be established to define the responsibilities, rights, and duties of the core hospital and other members, perfect the service quality management system, and enhance management efficiency. A council can be established to manage the hospital members.

- Implement the medical institutions’ functions and positions. The medical alliance should build a mechanism for hospital members to share responsibilities and interests and implement their respective functions and positions.

- Make steady progress to encourage residents to sign up for family doctor service. Training of general practitioner shall be enhanced. Hospitals in the medical alliance should step up efforts to push residents to sign up for demand-oriented family doctor service, and the service should firstly be available to patients with chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes, with old people, pregnant women, kids, and disabled individuals as the priority populations.

- Provide continued services to patients. Nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities are encouraged to join the medical alliance. A referral mechanism should be worked out so that patients recovering from acute diseases or surgery can be transferred to lower-level hospitals and continue to receive treatment and rehabilitation services. Hospitals can also join hands with nursing homes to provide one-stop convenient services from treatment to rehabilitation to long-term care.

How to improve mobility of premium medical resources within the medical alliance

The Guiding Opinions stated that under the premise of no changes in administrative status and fiscal support, hospitals can make unified allocation of staffing, wage distribution, and resource sharing to improve the mobility of premium medical resources among hospitals at different levels.

- Promote orderly flow of human resources. Efforts should be made to make unified allocation of medical resources to maximize the efficiency. Wage distribution within the medical alliance should be coordinated to motivate the medical staff.

- Lift grass-root hospitals’ service capacity. Tertiary public hospitals should serve as a leader in the medical alliance, and send experienced doctors to help grass-root hospitals enhance their service capacity by co-building special departments, clinical teaching, providing professional instructions as well as conducting joint project research and development.

- Build a unified information platform. Build a comprehensive public health information platform and develop separate platforms on hospital management and medical service management at province, city, and country levels, so that patients’ health records and electronic medical records can be archived, interconnected, and shared within the medical alliance.

- Make regional medical resources sharable among hospitals. The medical alliance may consist of a medical imaging center, a health examination & testing center, a sterilization & supplies center, and a logistics service center, so as to provide integrated services to all hospital members.

What policies should be introduced to build medical alliance

Building medical alliance is an extensive, longstanding, and complicated process that requires joint and persistent efforts by local governments and relevant departments.

- Further fulfill the government’s responsibility in providing healthcare services. The central government’s funding support for hospitals shall be increased to improve county-level hospitals’ ability to treat serious and complicated diseases and enhance the level of remote medical collaboration, so that medical alliance can play a more helpful role to grass-root hospitals.

- Further play the role of medical insurance as an economic leverage. The reimbursement ratio for insured patients getting treated at grass-root hospitals shall be increased, and the ratio for those seeking help at county-level and larger hospitals shall be reduced. This policy should encourage insured patients to visit grass-root hospitals more often.

- Optimize the staffing and incentive mechanisms. Medical institutions should be permitted to remove wage controls policies and use surplus revenue to reward staffers, and develop a wage distribution mechanism that ties staff wages to their positions and duties, job performance, as well as their actual contributions.

- Build a performance evaluation mechanism suitable for the medical alliance. The evaluation and institutional constraints shall be strengthened, and a sound indicator system to evaluate the effect of the medical alliance be established.

How to proceed with the construction of medical alliance in different areas

Building medical alliance is a systematic process that requires persistent efforts from four perspectives. The first is to strengthen organization and leadership—the local government should set up an interdepartmental task force to craft the top-level framework and draft supportive policies and a feasible implementation plan. The second is to clarify relevant departments’ duties and responsibilities—optimize drug pricing policies, overhaul the means of medical bills payment, implement fiscal subsidy policies, and support the construction of national clinical research centers and other medical infrastructures. The third is to step up supervision and evaluation—create a mechanism to assess the effect of the medical alliance, work out performance evaluation approaches and introduce accountability system. The fourth is to step up publicity and training efforts—Carry out policy training sessions for managerial and medical staff, and call for public media to beef up publicity of the hierarchical medical system and the medical alliance and improve public awareness and support.

Section 2: cases and experiences of medical alliance

History and experiences of medical alliances in foreign countries/regions

Status quo of medical alliances in foreign countries

After the end of World War II, hospitals in the developed world were struggling to deal with these challenges:

- rising medical expense. With the upgrade of medical instruments and development of advanced screening technologies, the demand for medical services was going up and sending medical expenses higher year by year (1). Besides, deteriorating air quality, changing disease spectrum, and population aging were also lifting the demand for healthcare services;

- inadequate government funding caused short supply of and unequal access to medical resources;

- internal problems such as absence of effective incentive mechanism, lacking of distinctions between different hospitals, and declined efficiency of medical services and public satisfaction were obvious (2);

- extremely low percentage of personal payment has caused excessive use of medical services and waste of private medical resources;

- the trend of privatization around the world, led by the US, has led to the boom of privately-run for-profit hospitals;

In order to promote flow of resources among hospitals and increase management level and service efficiency, hospitals have developed different forms of associations or alliances. Due to different policy environments and backgrounds at different countries and regions, they adopt different methods to integrate healthcare services.

Table 2

| Structures/means of associations | Virtual combination | Physical combination |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical integration | Service level network—e.g., in UK commissioned management—e.g., in Singapore, US, and Japan | Regional medical centers—e.g., in Australia |

| Horizontal-vertical integration | Group-like alliance—e.g., in Singapore | Integrated hospital group—e.g., in UK and Germany |

Virtual combination is a means of alliance that enables resource sharing through technology and management, whereas physical combination is a means of alliance under which assets are integrated to set up an independent legal entity and realize unified management. Horizontal integration indicates cooperation or alliance among the same type or level of medical institutions within a limited market of medical services. Vertical integration is an association of different types and levels of medical institutions within the same region or different regions, so that they can exchange information, complement resources, and share interests.

(i) Service level network.

Based on the level of medical demand in a region, a medical alliance can be classified into three-level or two-level medical network. The leveled network allows hospitals to focus on their specialties and functions and maximize the effects of their medical resources. In a three-level network, the primary community healthcare centers offer routine health services, the second-level hospitals provide treatment to patients injured by serious accidents or emergency patients, and the tertiary hospitals treat patients with emergency conditions or complicated diseases. Patients must first get treated at the primary (first-level) community healthcare center before they can be transferred to larger hospitals (3). For instance, Dawson is a standard and stringent three-level structure in the UK Under the structure, general practitioners provide basic healthcare to patients, specialists in the second-level hospital offer further consultations and treat transferred patients, while those in the tertiary (third-level) hospitals provide advanced therapies for rare or complicated diseases (4). Besides, UK has also adopted a series of policies and mechanisms to make sure the hierarchical medical system will be implemented, including standard management on general practitioners, extensive coverage of first treatment at community clinics, effective patient referral mechanism, stringent referral supervision mechanism as well as favorable medical insurance policies that encourages patient referrals. Japan has established a three-level circle—the first is outpatient clinics, the second is general hospitalization, and the third is less frequent but highly professionalized treatment (5). Sweden has built a three-layered medical network from community healthcare center to county hospital to regional hospital (6). Finland operates a similar network with vertical integration of medical resources from college-backed hospitals to community hospitals (7). Singapore is running a two-level medical network. The first level is community hospitals and general clinics offering basic healthcare services, and the second level are general or special hospitals offering comprehensive medical services and most hospitalization services (8).

The US also has a well-established three-level medical system. The extensive network of primary care is composed of private clinics, nursing homes, health education centers, and volunteer groups. The healthcare management system includes health insurance providers (insurers) and medical service providers (hospitals), and they use economic stimulus and organizational measures to balance the supply and demand of medical services. The economic stimulus measures make the two-way referral mechanism efficient and effective (9). There is another form of medical alliance in the US—Accountable Care Organization (ACO)—different service providers work together to provide all-around services to targeted populations (10).

(ii) Regional medical centers

Different from the service-level network, regional medical centers are independent legal entities. Australian government authorizes large public hospitals to manage community healthcare centers, rehabilitation facilities, home care centers, elderly nursing homes, and advanced medical examination & test centers, and these centers have separate functions and positions (7).

(iii) Commissioned management

Commissioned management is a means of trusteeship under which a medical institution is managed by its internal management team or a core hospital. The ownership of a trusted institution is separated from the right to operate. During the trusteeship, the nature and ownership of the medical institution remain unchanged. There are three types of commissioned management–trusteeship by private institution, by internal management team, and by a company.

For a trusteeship by private institution, a private institution will invest in and manage a public hospital by introducing corporate management philosophies and getting paid. For a trusteeship by internal management team, the hospital is operated like a company by independent administrators (2). Most hospitals in Japan are managed by private institutions or internal management teams.

Under corporate trusteeship, a hospital is operated and managed by a company to boost operating efficiency and cost-efficiency. Singapore and the US are typical markets of corporate trusteeship. HCA Healthcare Inc. introduces advanced management approaches, operating strategies, and medical technologies to hospitals it manages, and it has quickly become the largest hospital chain operator in the US (2).

(iv) Group-like association

Group-like association sets up a board of directors to manage and distribute medical resources (11). The group is governed by the board while day-to-day operations are headed by the president. The board is responsible for outlining the hospital’s development strategies, approving executive appointments and financial plans, and overseeing the quality of medical services. The group carries out unified management on finance, quality, medical materials, logistics, information system and education. Based on a horizontal-vertical mode, the group is composed of both hospitals at the same levels and those at different levels, forming two-way transferring mechanism inside it. Singapore has set up two large medical groups.

The Singaporean Ministry of Health has established the National Health Group and the Singapore Health Services to be separately responsible for providing medical services in the eastern and western parts of the country. These two groups are owned by the government but managed like a company (2). Both groups are independent legal entities and governed by their board of directors. CEO and board members are appointed by the government and report to the board. Day-to-day operations are headed by the group’s president, who is jointly appointed by the Ministry of Health and the group’s board (12). Public hospitals under the two groups are separate companies and they can make business decisions on their own. The government oversees medical practices and controls service prices, bed supply, and the purchase of expensive medical instruments. Large equipment will be purchased by a company controlled by the Ministry of Health, medicines will be bought by a professional pharmaceutical firm, and drugs used by hospitals will be supplied by professional medicine institutions (13).

(v) Integrated hospital group

Different from group-like medical alliance, an integrated hospital group is the product of hospital ownership integration, and the product is an independent medical group (13). The combined medical group remains a part of the government or a public-sector department, although it is managed like a company. The hospital group is governed by the board of directors, which formulate the overall development strategies and oversee policy implementations. Government representatives will join the board to reflect the hospital’s nature as a public-welfare entity (14). The group separates service buyers and providers and increases the hospital’s autonomy in the range of services, staff recruitment, equipment investment, financial arrangement, and day-to-day management, and reserves its right to seek profit and surplus. By introducing market mechanism, setting up medical groups can increase competition, reduce transaction cost, and strengthen hospital managers’ and staff’s sense of responsibility and enthusiasm, while the government can shift its focus to policy-making and regulation to improve the availability and equal access to medical services.

Let’s take a look at the combination of 10 public hospitals in Berlin and the UK’s Hospital Trust. The ten hospitals are independent legal entities and structured like companies. Every hospital has a board of directors, with half of the board members nominated by the government and the other half nominated by staff. The board appoints Chief Executive Officer to take charge of day-to-day operations (2). For the UK’s Hospital Trust, hospitals are independent legal entities and managed by an independent board, which can launch public recruitment process to select a president to manage the hospital. Hospitals are owned by the government but managed by professional executives under the leadership of the board of directors/supervisors (15).

Due to continued expansion of for-profit hospitals, market forces are pushing more hospitals to be privatized. For instance, Rhön-Klinikum Aktiengesellschaft (RHK AG) has become a large medical group with 53 hospitals across nine German states, thanks to its sustainable horizontal acquisitions, vertical resource integration, excellent management team as well as the most optimal medical service procedures (16). Backed by aggressive expansions in the international market and coordinated development of chain pharmacies and clinics, Apollo Hospitals has become the first incorporated private hospital operator in India (17).

Development trend of medical alliances in foreign countries/regions

For the development of medical alliances in developed countries, various models can convert into each other. As hospitals gain a greater autonomy, loosely-organized medical alliances become closely-organized ones via asset integration, and online ones extend to offline; horizontally-integrated medical groups tend to enhance vertical cooperation to transform to a mixed model. The development trends of foreign medical alliances include:

- Clarification of property rights. The property right system of hospitals should be reformed to clarify property ownership. Specifying the rights to usage, usufruct, and transfer of hospitals can regulate the practices of hospitals and improve the allocation of resources. Therefore, the clarification of property ownership and trimming transaction cost are vital to the reform of hospital property rights.

- Risk diversification and business expansion. Hospitals adopt unified and effective allocation of medical resources including talents, funds, and materials and diversify risks via expansion in forms such as internationalization. The expansion of hospitals creates economies of scale, circumventing adverse effects of the market mechanism. In Canada, hospitals and other medical institutions are increasingly integrated with each other, expanding the coverage of family practice and medicine (18). Britain’s hospital trusts consider further expanding to include purchasers of their affiliated medical institutions and family doctors in a bid to increase gains. Meanwhile, it is helpful to change the status quo where the establishment of medical groups is exclusive to private medical institutions and individual practitioners (19).

- Diversified fundraising channels. Diversified fundraising channels support private hospitals’ heavy investment in infrastructure development, medical equipment, and information networks. The involvement of private investment can tie up investors with hospitals, introduce competition and advanced management models, improve the efficiency of public hospitals by changing operating model and enhancing management, and create a healthy business environment to achieve win-win outcomes for governments, hospitals, and investors. In Hong Kong SAR, alliances between public and private medical institutions have been established in compliance with government policies.

- Optimizing incentive mechanisms. Reasonable remuneration systems and effective internal incentive mechanisms, such as annual salaries and promotions, should be devised for doctors in addition to their base pays, so as to ensure that doctors are paid remunerations commensurate with their devotion and performance, and thus lead a decent life and work efficiently.

- Patient-oriented services. Hospitals offer people-oriented, one-stop services to facilitate patients and their family members; train employees, and set up incentive mechanisms and continued study systems to improve employees’ medical skills and comprehensive capabilities; and supervise the quality of medical services and establish complaint offices to settle disputes between doctors and patients. In Canada, medical services are patient-centered. Special medical staff are arranged to meet the demands of patients; diagnosis, medical services, lab services are tailored for different patients; and administrative staff provide support (18).

The establishment of medical alliance is a complicated process, and many areas in China have made various efforts in this aspect. However, domestic medical alliances lack diversified models and face institutional restrictions. The development of foreign medical alliances is a good reference for domestic ones, but it will be unwise to borrow foreign experience without adjustment in view of different health systems. China should establish medical alliances with local characteristics.

History and cases of medical alliances in China

History of medical alliance in China

In the four decades since China’s reform and opening-up, big cities are offering far better medical services than elsewhere, causing over concentration of medical resources in these cities, and the number of urban population has risen at a faster pace. Since 2003, the central government has increased investment in new countryside, urban construction and medical care, to balance economic development and narrow the development gap via financial support. Around 2007, Shanghai planned to establish medical alliance, with emphasis on vertical integration of medical resources. The goal was to realize hierarchical diagnosis by linking third-grade, second-grade and community hospitals to provide integrated disease management from hospitalization to outpatient service to recovery, improve equal access to medical services and promote gradual downward mobility of quality services. However, the plan was put on hold due to problems such as medical insurance payment, fiscal support and property rights ownership. Yet, the establishment of medical alliance is inevitable. State policies were rolled out in 2010 to encourage large hospitals in big cities to transfer medical resources, talent and technologies to small cities in order to address the inequality and enable local residents to enjoy quality medical services.

In 2009, the Shanghai municipal government proposed to set up two regional medical alliances in Ruijin Hospital Luwan Branch and Xinhua Hospital Chongming Branch. The Ruijin-Luwan Medical alliance, established on March 21, 2011, adopts the “3+2+1” closely-organized model and has a board of directors. As the top decision-making body, the board is mainly responsible for mapping out overall development strategies, resources allocation and medical insurance quota distribution of member hospitals as well as implementing the accountability system of directors. Seven hospitals, including Ruijin Hospital, two second-grade hospitals and four community health service centers, operate in the form of medical alliance to jointly optimize medical services in the region and improve hierarchical diagnosis services. The medical union encourages soft mobility of medical staff among its members. Department leaders at Ruijin Hospital are department directors at second-grade hospitals so as to improve the region’s medical service quality. Meanwhile, residents can make appointments with experts from Ruijin Hospital at community health service centers in Luwan. In order to solve the difficulty in hospitalization, the beds in the union will be reconfigured. To lower the expenditure of medical treatment, a regional examination/testing center and imaging diagnostic center will be established inside the medical union. The residents can make an appointment for health check-up in the community hospital, and the results are valid in the whole union.

The concept of medical alliance proposed by the National Health and Family Planning Commission is more inclusive, including such forms as vertical medical alliance of city hospitals, regional medical communities at county level, medical alliance of special hospitals, regional medical unions of special hospitals and general hospitals’ relevant departments, and cross-region remote network of medical cooperation.

Example of urban medical alliance—Shenzhen Luohu medical group (closely-organized medical alliance)

- Background: It has been a thorny issue to mobilize medical resources downward to community health centers (CHCs) to improve their medical services and attractiveness to patients. In Shenzhen, most CHCs are still established and managed by hospitals and difficult for intensive management, which creates a big barrier for implementing two-way referral, hierarchical diagnosis, and downward mobility of medical resources in Luohu District. In 2014, the district government invested RMB 650 million yuan in medical infrastructure, manpower and equipment, and digitalization. Despite the heavy investment, the district still faces medical resource shortage, unbalanced structure of medical resources, inadequate use of advanced medical technologies and poor services.

- Establishment time: August 2015.

- Initiator: The Third Hospital Affiliated to Shenzhen University (Luohu District People’s Hospital).

- Members: Five public hospitals and 35 CHCs in Luohu district.

- Cooperation model: Corporate governance structure (one legal entity—Luohu Hospital Group).

- Goals: To strengthen CHCs, improve residents’ health, and reduce patient populations.

- Operating model: Six resource-sharing centers and six administrative centers were established to integrate medical resources in the region and reduce operating costs. It is worth mentioning that the medical group promotes talent sharing, technical support, mutual recognition of health check results, prescription sharing, and service connection. Work experience at CHCs is taken into account in medical staff’s qualification assessment and promotion. Subsidies are provided to encourage lectures at CHCs, free clinical services, outpatient services by non-CHC experts, and outpatient services by CHC experts on rest days, in order to make expert visits to CHCs a routine. These experts should go to CHCs to offer community residents with services including medical treatment, prevention, healthcare, mental disease prevention and control, and chronic disease prevention and treatment.

- Achievements: In 2016, the number of patients receiving diagnosis and treatment at CHCs managed by Luohu hospital group jumped 94.6% from the previous year, with the proportion of insured patients up from 51.47% to 60.3%.

Example of county-level medical communities—“Anhui Tianchang” medical community

- Background: Before the introduction of “medical communities” in Tianchang City, county-level and township hospitals were polarized. County-level hospitals were overcrowded with patients, while township ones only saw few visitors. To solve the problem and establish a smooth hierarchical diagnosis system, the city attempted to set up “medical communities”.

- Establishment time: 2014.

- Initiators: Three second-grade hospitals in Tianchang City.

- Members: Sixteen township health centers and 163 village health clinics.

- Cooperation model: “Four in One” regional medical community. Specifically, the “medical community” is of shared services, interests, responsibilities and development. The four aspects are interrelated and influence each other.

- Goals: Encourage vertical integration of medical resources, improve the urban-rural medical service system, and improve medical services at county and township levels; mobilize stakeholders to engage in medical reform, and the shared interests of a “medical community” means equal interests of community members gained through the allocation of medical insurance funds.

- Operating model: The “community of shared services” capitalizes on respective advantages of medical services at county, township and village levels to produce synergy between prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation. The “community of shared responsibilities” delineates the service scope of county-level public hospitals and township health centers, such as disease catalogues for admissions in the two kinds of medical institutions as well as 41 diseases referred to lower-level medical institutions by county-level hospitals and 15 diseases for downward referral during the rehabilitation period. The “community of shared development” refers to the coordinated development of community members. Higher-level hospitals should enhance instructions to lower-level hospitals to improve their medical services. Besides, “medical communities” also encourage “1+1+1” master and apprentice relationships between village doctors and doctors at township- and county-level hospitals. In the construction of the “community of shared interests”, medical insurance funds adopt a system of prepayment per head based on “medical community”, under which the overruns are covered by county-level hospitals while the balance is distributed to county-level hospitals, township health centers and village clinics at 6:3:1. In order to avoid possible shortage of services under the system, the city also introduces payment by clinical pathway and payment by disease, and implements floating quota-based payment of medical insurance according to the proportion of diseases and the implementation of clinical pathways, so as to standardize services at the “medical community”, control medical costs, and refer patients to lower- or higher-level hospitals.

- Achievements: As the end of October 2016, the outpatient rate in Tianchang reached 92.24%, up more than 1 percentage point from the previous year; the self-paid medical fees by patients declined RMB 331; a satisfaction survey by a third party found that the patient satisfaction of two public hospitals remained above 92%.

Example of special medical association—Beijing Children’s Hospital group

- Background: “The long queue before the Beijing Children’s Hospital can reach the West Second Ring Road. Many patients sleep in tents so that they can get a better chance to make an appointment the next day”. About 60% of ill children were non-natives. As long as children don’t feel well, be it ailment or severe disease, families will crowd the hospital, increasing the burden on doctors.

- Establishment time: May 31, 2013.

- Initiator: Beijing Children’s Hospital.

- Members: The number of the group’s members has risen from nine to 722, mainly in the northern, southern, southwestern and central provinces. The group has become the largest cross-province medical alliance in China.

- Cooperation model: Beijing Children’s Hospital is at the center of the cooperation, which consolidates advantageous medical resources of provincial children’s hospitals, upholds the philosophy of “shared experts, clinical services, researches and teaching”, adopts the model of “doctors go to see patients”, and establishes a third-grade hospital network featuring horizontal coordination and vertical extension of quality medical resources, with an effort to ensure equal access to excellent medical teams for patients from the rest of the country.

- Goals: Improve medical services at grass-root hospitals via paired support; refer more patients with complicated diseases to big hospitals so as to connect departments of alliance members.

- Operating model: Choose a hospital with strong expertise as the initiator to help grass-root hospital improve specialized medical services and build “resident medical teams” to turn traditional aid into long-term cooperation; improve the comprehensive capability of member hospitals and the quality of national pediatrics via academic exchanges, scientific platforms, joint construction of departments, remote consultation, and tours of experts, enabling patients to enjoy first-rate medical services without the need to leave their province. Group members share experts, clinical services, scientific researches, teaching and prevention measures as well as establish remote consultation centers to reach the goal of “doctors go to see patients”.

- Achievements: Since its establishment in 2013, the Beijing Children’s Hospital group has basically formed a joint service model of “preliminary diagnosis at grass-root hospitals, remote consultation on complicated diseases, and seamless referral of severe patients”, laying the foundation for the hierarchical diagnosis of pediatrics. A group of 155 experts, including 12 (or 13) from the Beijing Children’s Hospital, tours the country to give lectures. Now, the medical alliance covers 722 grass-root hospitals. To improve the pediatric medical system, members of Beijing Children’s Hospital group have established local pediatrics alliances since 2015, extending the network to cities and counties via provincial children’s hospitals. Following the establishment of the group, the number of outpatients at children’s hospitals in Henan, Hebei, Shandong and Anhui has risen substantially. A pediatric medical network covering national, provincial, municipal and county hospitals has been set up, laying a solid foundation for the hierarchical diagnosis system of pediatrics (20).

Example of regional medical unions—Shanghai pediatrics medical alliance

- Background: During the 2011–2015 period, Shanghai made efforts to enhance children health services as the medical reform advanced, such as establishing Shanghai Center for Women and Children’s Health and the Putuo branch of Shanghai Children’s Hospital, expanding pediatrics departments of municipal general hospitals, raising the proportion of beds at obstetrics and pediatrics departments of new hospitals built under the suburban “5+3” program to 10% of the total, adding 345 beds at pediatrics departments of Xin Hua Hospital and Tongji Hospital, and mobilizing the private sector to construct 15 pediatric hospitals. In order to support pediatric medical services in the suburbs, Shanghai Children’s Hospital established the city’s first pediatrics union “Shanghai Children’s Hospital Putuo Pediatrics Union” in November 2012, and formed the Jiading Pediatrics Union and Jing’an Pediatrics Union in June and September 2014 respectively. In 2016, the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning issued the “Special Plan for Enhancing Services for Children’s Health”, requiring that general hospitals of second grade or above should set up pediatrics departments and CHCs should also provide pediatric services; three famous children’s hospitals, including Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, should add beds. In late January 2016, the Shanghai municipal government convened a press conference, proposing to establish five regional pediatrics alliances or unions before 2020.

- Establishment time: April 2014–September 2016.

- Initiators and members: Fourteen community hospitals led by Shanghai Children’s Hospital Center in the east; 13 community health service centers, the Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital and Central Hospital of Minhang District led by Children’s Hospital of Fudan University in the south; 16 second-grade and third-grade district hospitals led by the alliance between Shanghai Children’s Hospital and health and family planning commissions of Jing’an, Putuo, Jiading and Changning in the west; 13 second-grade and third-grade hospitals and 23 community health service centers led by Xin Hua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in the north; Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, the health and family planning commission of Huangpu district and Shanghai Children’s Hospital in the middle.

- Cooperation model: To integrate resources of pediatric diagnosis & treatment and disease prevention of relevant medical institutions to realize “diagnosis and treatment of common diseases at grass-roots medical institutions, solutions to complicated and critical diseases within the medical alliance”, establish cooperation between medical institutions at all levels, and maximize the efficiency of using pediatric medical resources; enable children patients to receive quality, convenient and continuous diagnosis and treatment in their communities via medical alliances of hospitals affiliated to universities; attempt to establish expert offices specializing in treating childhood asthma, congenital heart disease, and orthodontics; provide training based on technologies of leading hospitals; and combine pediatric medical resources of second-grade hospitals and community health service centers.

- Goals: Capitalize on initiators’ brand effects and advantages in treatment, teaching, scientific research and disease prevention to integrate resources of pediatrics and healthcare for women and children from relevant medical institutions in the region so as to improve pediatric services; promote homogeneous development of members via such forms as standard equipment, unified training and formulation of rules; send academic directors to set up joint pediatric wards for resources sharing; maximize the utilization and expansion of pediatric medical resources to improve regional medical services for children and provide safe, effective, affordable, all-round and continuous medical services; take measures to divert children patients to local medical institutions in a bid to realize the development goal of “diagnosis and treatment of common diseases at grass-root medical institutions, solutions to complicated and critical diseases within the medical alliance” and eventually mitigate the supply-demand unbalance of pediatric services; and conduct vertical integration of pediatric medical resources to offer local children with quality and convenient medical services, support pediatrics departments of second-grade and third-grade general hospitals in the region, and train pediatric talent.

- Operating model: Carry out “seven measures”, namely building regional pediatrician teams, establishing diagnosis and treatment centers for common pediatric diseases, constructing regional platforms for shared information on pediatric diagnosis and treatment, improving the capability of treating children with severe diseases and newborns with critical diseases, promoting multi-center children’s health-related treatment and prevention programs, enhancing sharing mechanisms for pediatric check resources, and promoting the joint development of pediatrics and maternal and child health; promote unified diagnosis and treatment routines, professional training, and medical information disclosure; and achieve the coordination of referral and consultation, special checks, clinical quality control and children’s health management. Shift from traditional development model, cooperation model and treatment model toward all-round cooperation between member hospitals’ pediatric departments in clinical practices, teaching and scientific research through three steps - homogeneous management, strength development and brand building. Unify recruitment standards and training programs for directors, doctors, nurses and technical staff of pediatric departments as well as roll out “Diagnosis and Treatment Standards of Pediatrics Medical alliance” and “Nursing Standards of Pediatrics Medical alliance” with an aim to implement homogeneous management and improve the overall strength of pediatrics. Set aside funds for the training of front-line pediatric staff to improve grass-root pediatric services and ensure equal access to medical services; promote demonstrative pediatric outpatient services and two-way mobility of staff, unify signs and operating procedures, encourage outstanding doctors to visit local communities and promote the homogeneous diagnosis and treatment of common pediatric diseases; create emergency fast tracks with emphasis on the transfer of critically ill newborns and first aid to children with severe diseases; promote regional public health services for children, including newborn disease screening, intervention in the development of high-risk infants via follow-up visits, prevention of children’s accidental injuries, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and scoliosis screening; advance online children’s health services by setting up platforms for sharing medical information and resources, enhancing the digitalization of the referral of patients with complicated diseases, remote video consultation, research cooperation and big data analysis as well as software and hardware support and formulation of pricing standards; promote the reform of medical insurance payment system to adopt capitation. Further promote hierarchical diagnosis and two-way referral to improve the region’s clinical pediatric skills and services, enabling children patients to enjoy first-rate services.

- Achievements: The East Pediatrics Medical Union, which was initiated by Shanghai Children’s Hospital Center in collaboration with Pudong and Fengxian districts, has 41 members. In 2016, the number of outpatients at union members’ pediatrics departments increased 4%, while the growth of the Shanghai Children’s Hospital Center slowed by 10–15% from 2015, which means that other hospitals in the medical union took more share of pediatric services in the region. In the southern area, the medical union led by Children’s Hospital of Fudan University gained new development opportunities. Union members have 1,500 beds in total, with the annual number of outpatients exceeding 3 million and the number of discharged patients reaching 50,000. The union’s network covers the downtown area as well as nine suburban districts, including Minhang, Xuhui, Huangpu, Yangpu, Jing’an, Pudong, Qingpu, Baoshan and Jinshan.

Example of remote medical cooperation—China-Japan Friendship Hospital health alliance

- Background: China-Japan Friendship Hospital took the lead to explore remote medical services. In 2012, the hospital was approved to set up the “Ministry of Health Center for Remote Medical Service Management and Training”, mainly responsible for offering remote medical services and formulating relevant policies, systems and standards. The China-Japan Friendship Hospital Health Alliance was established under the aegis of the Chaoyang health bureau as required by the “Guidelines on the Establishment of Pilot Regional Medical Alliances in Beijing” (No. 182 of 2013) jointly issued by the Beijing health bureau and other departments as well as the “Guidelines on the Coordination Mechanism for Regional Medical Services by Medical Institutions in Chaoyang District” (No.256 of 2012) and the “Circular on the Implementation Measures for Regional Medical Alliances in Chaoyang District (Trial)” (No. 134 of 2013) issued by the Chaoyang Health Bureau.

- Establishment time: December 26, 2013.

- Initiator: China-Japan Friendship Hospital.

- Members: Core hospital and cooperative hospitals (including tertiary/second-grade hospitals and community health service centers). The core hospital is China-Japan Friendship Hospital, and the cooperative hospitals include Wang Jing Hospital of the China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (CACMS), Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Third Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University Affiliated Aviation General Hospital, Beijing Capital International Airport Hospital, Beijing Geriatric Hospital, as well as community health service centers in Olympic Village, Asian Games Village, Laiguangying, Sunhe, Wangjing, Donghu, Taiyanggong, Xiangheyuan, Anzhen, Dongba, and Heping Street. All alliance members will put up a sign of “China-Japan Friendship Hospital Alliance Member” after the alliance is formally established.

- Cooperation model: Cooperation across administrative areas, affiliations, and ownerships. China-Japan Friendship Hospital is directly managed by National Health and Family Planning Commission, Wang Jing Hospital is affiliated to the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Third Affiliated Hospital to the Ministry of Education, China Medical University Affiliated Aviation General Hospital to Aviation Industry Corporation of China, Beijing Capital International Airport Hospital to Beijing Capital International Airport Co., Ltd., and Beijing Geriatric Hospital to Beijing Civil Affairs Bureau. The medical alliance covers more than 1.5 million people in the east of Chaoyang district and has 4,460 beds in total.

- Goals: Uphold the basic principle of “government leadership and autonomous choice, three-level network and tiered positioning, coordination between hierarchical diagnosis and convenience, and shared interests and responsibilities” to establish a united and practical medical alliance with members bonded together by business, information, management and interest.

- Operating model: Through the remote medical service networks consisted of initiators and medical institutions in grass-root and underdeveloped areas, public hospitals provide remote medical services, remote teaching and remote training to these areas, promote the vertical mobility of resources via digital channels, and improve the accessibility of quality medical resources and efficiency of medical services. Alliance members with specific responsibilities should work closely together with each other. The core hospital is responsible for the diagnosis and treatment of complicated and critical diseases, the application of high medical technologies and instruction on cooperative hospitals. Tertiary hospitals are responsible for the diagnosis and treatment of some critical diseases and complicated diseases and the application of common diagnosis and treatment technologies. Priorities are given to the following five tasks. The first one is paired support. Some departments are selected to form alliances to help each other according to the characteristics and demands of alliance members to improve the capabilities of the members via outpatient services by experts, ward rounds, case discussions, tutoring, and training. The second is to implement two-way referral. Fast tracks for referred patients are established within the alliance based on the principle of respecting patients’ willingness, complying with medical insurance policies, allocating medical resources properly, and providing continuous services and health management. Two-way referral procedures and systems should be established to ensure proper mobility of patients within the alliance in view of patients’ conditions and members’ functions and advantages. The third is to conduct remote consultation. The medical alliance should set up imaging diagnosis centers and conduct remote consultation on radioscopy via remote medical education platforms. The fourth is to enhance talent training. Talent training programs should be devised to include courses of general practitioners, special skills and nursing. Expert groups should be formed to tour grass-root hospitals to guide their service quality management, hospital administration, and hospital-acquired infection prevention and control as well as to tutor grass-root doctors. The fifth is to increase information support. Online information sharing mechanisms should be established via remote medical education platforms to realize information sharing on appointments, referral, consultation statistics, mutual recognition of check results and remote consultation.

- Achievements: With the development of “Internet+”, remote medical services are expanding as well. Statistics show that China-Japan Friendship Hospital conducted remote consultation on more than 5,000 patients in 2015 and 2016 respectively, and the number will be much bigger this year. Now the hospital has forged alliance with over 2,000 medical institutions across the country. The scope of remote medical treatment has expanded after years of development, including remote training and education in addition to remote consultation.

Forms of participation in medical alliance by private hospitals

In 2010, the Guidelines on Further Encouraging and Guiding the Private Sector to Run Medical Institutions enhanced support for private investment in medical institutions. By 2015, the number of beds and services provided by non-public medical institutions accounted for 20% of the total (21). In recent years, private hospitals have made positive attempts to establish medical alliance. There are two models suitable for private hospitals: one is to form closely-organized medical groups via such forms as acquisition, contract or custody to run a chain of private hospitals, which share medical resources and patient archives, allow referrals and improve professionalism on condition of guaranteed interests; the other one is to jointly establish medical institutions under corporate governance structure by the private sector and experienced public hospitals (22). Although the government has rolled out multiple policies to encourage private investment in hospitals, supportive systems in such aspects as access, approval, talent, taxation and funds, still lag behind, leading to weak development of private hospitals. Particularly, the talent system, which is decisive to hospital development, is flawed. The lack of effective ways to attract talent, shortage in talent reserves, unreasonable talent structure and high talent turnover are weaknesses of many private hospitals and also hinder the participation of such hospitals in establishing medical alliance. The following is an example of cooperation between public and private hospitals.

- Background: The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University and Pingyangxian Chang Geng Hospital forged an instruction-oriented cooperation between public and private hospitals. With its brand effect, talent and technological advantages, the former provides resources of brand, technology and management experience, and cooperates with the latter to cultivate the medical services market.

- Establishment time: September 2006.

- Partners: The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (core hospital) and the Pingyangxian Chang Geng Hospital (partner hospital).

- Cooperation model: The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University provides technology and management experience, while Chang Geng Hospital offers its building complex as the medical treatment base. The jointly-run hospital retains its joint stock ownership system, but adopts the mission, philosophy and standards of the public hospital. The direct management organization is the comprehensive management office, responsible for the coordination and communication between leaders of the two hospitals. The core hospital dispatches a certain number of outstanding employees (about 100 at the early stage) to the jointly-run hospital as well as sends a certain number of experts to offer outpatient services regularly. The two parties distribute interests according to an agreed proportion. The first stage of cooperation lasts for five years as stated in the cooperation agreement.

- Achievements: (i) Optimize the allocation of public hospitals’ special assets. Public hospitals usually have a strong influence for their management model, technological brand and medical resources to create their own special assets. The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University enjoys a high reputation incomparable by ordinary medical institutions in the south of Zhejiang and the northeast of Fujian. In contrast, the reputation of the private hospital is deteriorating due to loose internal management, and it is difficult for the hospital to form its special assets. The public hospital sends medical talent to its private partner and adopts a vertical management model, which can help enhance patients’ confidence in the jointly-run hospital. Statistics of performance in the first two months showed that the jointly-run hospital saw rising outpatients and hospitalized patients, including medical staff and their family members at other medical institutions in the region; (ii) Improve economic benefits substantially. The cooperation model increases economic benefits significantly. The first is the benefits of economies of scale. The public hospital and the private hospital are tied up together in both technology and management. The private hospital can thus receive free technical support and training, medical equipment and management experience, while the public hospital gains greater influence and more medical staff and devices. The cooperation reduces medical service costs of both parties, achieving economies of scale. The second is the benefits of economies of speed. The new cooperation model changes labor distribution and introduces strict competition mechanism, which surely improve the work efficiency of employees. Meanwhile, a new referral system under the model speeds up the response to different sources of patients, producing benefits as well. The third is the benefits of information economy. A study shows that “the relations of private hospitals with local communities and other medical institutions are far better than that of public hospitals, which however get along better with health regulators”. The public-private cooperation facilitates the two sides to exchange information on medical policies, industrial development, medicine and technological development; (iii) Cooperation brings about social benefits. With rising living standards in recent years, some affluent people in non-urban areas also have demands for high medical consumption, shifting focus from medical treatment to medical care and prevention. A jointly-run hospital with comprehensive functions can meet the public’s demand for medical treatment as well as the affluent people’s diversified demands for medical care and prevention, offering them with easy access to quality health services. Time is decisive to some critically ill patients, especially old-age patients with chronic diseases, and treatment at nearby hospitals is the best choice. The patients can receive quick and safe treatment at the jointly-run hospital. Chang Geng Hospital is located near the National Highway 104, and often receives patients injured in car accidents. In the past, the hospital was unable to deal with such patients due to various limitations. Following the cooperation with the public hospital, the hospital can treat such patients and sees a high proportion of discharged patients. According to statistics in the first two months since cooperation, the number of patients rescued from critical conditions exceeded 50 (23).

Chapter two: cooperation among hospitals in the field of mental health and development of mental health alliances

Section 1: resource allocation for mental health in china: status quo and issues

With its rapid socio-economic development, China is facing accelerated industrialization, urbanization, marketization, and population aging, which have led to increasingly severe mental problems. Mental health has become a major public health issue and social problem affecting socioeconomic development (24). In 2004, there were 16 million people with mental disease in China, and the prevalence of various mental disorders reached 13.47 per thousand. It has the highest total disease burden in China, accounting for about 20%. It is estimated that by 2020 the proportion of neuropsychiatric diseases will rise to 25% the total disease burden in China (25). On the other hand, the currently available resources and capabilities in China are far from adequate. The distribution of mental health service resources in China is uneven. Most of the major mental health facilities and professional physicians are located in provincial capitals and other large cities. A large number of patients with mental diseases have no access to timely and effective treatment and rehabilitation, which not only seriously affects the quality of life of patients and their families but also places a heavy burden on society. New ways and more effective methods are urgently needed to address these issues.

On May 1, 2013, the Mental Health Law of the People’s Republic of China was formally enacted. The mental health law stimulates that mental health shall be led by the people’s government at or above the county level and should be incorporated into the national economic and social development plans. Efforts should be made to establish and optimize the prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation service systems for mental disorders, establish and improve the coordination mechanism and accountability systems for mental health, and assess and supervise mental health work undertaken by relevant authorities. Meanwhile, it is important to encourage and support talent training, maintain their legal interests and rights, and enhance capacity-building (26). The promulgation and implementation of the Mental Health Law has greatly promoted the development of mental health prevention and control in China.

Distribution of mental health facilities in China

The number of mental health facilities in China has increased annually since 2005. In 2008, China formulated the “National Guiding Outline for the Development of the Mental Health Service System (2008–2015)”, followed by laws and regulations including “Regulations on the Management of Severe Mental Diseases (2012 Edition)” and “Mental Health Law”, proposing specific goals, norms, and requirements for mental health services. Since 2009, the State has increased investment in mental health, and the infrastructure and talents of psychiatric hospitals have been strengthened, and the mental health industry has entered a stage of rapid development.

In 2010, there were a total of 1,650 mental health facilities in China, of which 874 were psychiatric hospitals (Table 3), 604 were departments of psychology/psychiatry in general hospitals, 77 were rehabilitation centers, and 95 were clinics. Of these 1,650 institutions, 1,146 (69.45%) were sponsored by the government (including 892 by health authorities, 183 by civil affairs departments, 2l by public security systems, and 50 by other authorities including judicial departments and family planning commissions), 243 (14.73%) by private sector, 195 (11.82%) by enterprises, and 66 (4.0%) by other institutions such as public institutions and social organizations (Table 4).

Table 3

| Year | Number of specialist psychiatric hospitals | Growth rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 557 | – |

| 2006 | 570 | 2.33 |

| 2007 | 577 | 1.23 |

| 2008 | 598 | 3.64 |

| 2009 | 637 | 6.52 |

| 2010 | 874 | 37.21 |

| 2015 | 1,235 | 41.30 |

Table 4

| Sponsor | Year of 2010 (n) | Year of 2015 (n) | Growth rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government | 1,146 | 2,138 | 86.56 |

| Private | 243 | 655 | 169.55 |

| Enterprises | 195 | 136 | −30.26 |

| Others | 66 | 7 | −89.39 |

The majority of the government-sponsored institutions are psychiatric hospitals (n=677, 59.08%), which are mainly sponsored by municipal administrative authorities (n=496, 43.28%), and only 26 institutions (2.27%) were at or below the county level.

According to China’s administrative divisions, 28 of 333 prefectures/cities still had no psychiatric beds by the end of 2010; among the 2,856 districts/counties across China, only 970 districts/counties had psychiatric beds, and two thirds of districts/counties still had no psychiatric beds (27).

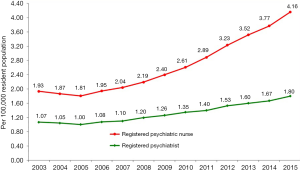

According to the National Health and Family Planning Commission, there were 2,936 mental health facilities in China in 2015, an increase of 77.94% over 2010. These facilities included departments of psychiatry in general hospitals (n=1,268, 43.19%) in general hospital psychiatry, psychiatric hospitals (n=1,235, 42.06%), grass-root health care institutions (n=293, 9.98%), general clinics (n=53, 1.81%), mental health clinics (n=44, 1.50%), and rehabilitation centers (n=43, 1.46%). The sponsors of these facilities included government authorities 2,138 (72.82%) are headed by government departments, and are in charge of government departments, including 1,855 health care plans, 208 civil affairs officials, 19 public security officers, and other government departments (education, disabled persons’ associations). There were 56 companies in the armed forces, armed police, and the judiciary; followed by 655 private enterprises (22.31%); 136 enterprises (4.63%); and other organizations (trade unions, social organizations, collective ownership) were the least, only 7 (0.24%).