The effect of economic workplace stressors on health outcomes

Introduction

Negative health outcomes in relation to stress is a well-covered topic. Health outcomes in relation to workplace stress is even more so. What this author wishes to focus on in this review is:

- Examples of economic workplace stressors;

- The historical context behind those stressors;

- Contextualization of those stressors in 2020;

- The physiological response to acute/chronic stressors and;

- Cite interventions to alleviate economic stressors.

Materials and methods

This review was compiled from pre-existing contemporary research, government data and news reports in order to showcase the state of the public health within the U.S. workplace. Pre-existing studies utilized in this review have been featured previously in predominant medical journals and nationally circulated news publications. This review is based on studies and reports published on the evolution of the U.S. workplace and the role of stress in public health roughly over the past 50 years from about 1970 to current day.

Results

Types of workplace stress

There are many stressors in the workplace. Physical ailments are more associated with manual labor and repetitive motion. For example, truckers and those who drive long distance are at increased risk for lower back problems such as vertebral disc hernias and osteoarthritis due to the vibrations generated as the vehicle moves along the road. Jobs which require repetitive motion, such as factory assembly line work and typing increase the likelihood of repetitive motion injuries such as carpal/tarsal tunnel syndrome. Also, jobs which require workers to be in a seated position all day increase the likelihood of vascular coagulation and deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Though physical ailments are mainly specific to manual labor, all jobs come along with emotional stressors such as:

- Heavy workloads;

- Long hours;

- Deadlines;

- Organizational culture/bullying;

- Job insecurity;

- Lack of opportunities for career advancement;

- Little workplace autonomy, etc. (1).

Wages and hours worked

Wages and hours worked are specific economic stressors that come along with all employment. The reason why wages are considered to be an economic stressor is relatively straightforward. If your wages are low, then you have less money. For the purposes of this discussion, workplace benefits such as retirement will be considered to be another form of wage as well. The current federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour. That’s about $15,080 annually. However, workers whose state mandates a higher minimum wage must be paid at the state’s going rate (2).

Hours worked is also considered to be an economic stressor because you have less time to dedicate to your personal responsibilities as the number of hours you work increase. For example:

- You may need to hire childcare in order to take care of your kids because you can’t personally do it.

- You may have neglected to get preventative care because you didn’t think that you had the time. Neglecting to get this year’s flu shot may have resulted in you getting sick and having to take additional days off from work. Neglecting your shortness of breath may have resulted in a trip to the emergency room for chest pain and medical bills, etc.

The current federal limit on hours worked per week is 40 hours. However, a growing number of workers exceed this number of hours due to the rise in contract work (such as Uber drivers), temporary positions and “off the books” positions (3).

The productivity-pay gap

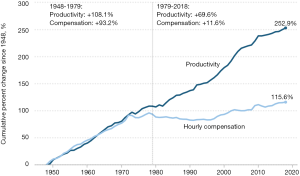

Historically, prior to the 1970’s, there was a linear association between wages and people’s productivity in the workplace. However, after around 1973, a discrepancy arose between the two as shown in Figure 1.

As showcased in the graph (Figure 1), productivity after 1973 continued to rise as it always did. However, wages began to stagnate. The area between the productivity and wage curves is known as the “productivity-pay gap” (4).

Historical sources of the productivity-pay gap

The productivity-pay gap is a source of contention among economists. The data is clear but what could be responsible?

- In the 1970’s, corporate influence became a major factor in the realm of politics. Corporations began to dedicate more and more resources towards lobbying efforts in order to influence lawmakers to craft favorable legislation towards industry (5). Supreme Court decisions, such as Buckley v. Valeo [1976] and Citizens United v. FEC [2010], cemented corporate influence in politics by setting the legal precedent that money in politics is considered to be free speech (6,7).

- Prior to 1971, the external value of foreign currencies was fixed in relation to the dollar whose own value was backed up with gold at the rate of $35 per ounce (Bretton-Woods system). This means that the total amount of money in circulation could be no greater than the amount of gold held in the Federal Reserve. However, under President Nixon, this standard was done away with due to concerns that an overvalued dollar might undermine the United States’ international trading status. Subsequently, the current practice of floating exchange rates was adopted (8).

- After World War II, there was a concerted effort by the federal government to undermine the position of worker’s unions. The 1947 Taft-Hartley Act got rid of the requirement that employees had to join a union as a condition of employment (9). Withdrawal from the Bretton Woods System in the 1970’s led to rapid inflation and rising interest rates which decimated the manufacturing sector. Due to the consequent high unemployment which resulted from this economic instability, workers in the manufacturing sector became more willing to work for lower wages and accept nonunionized roles (10). There are negative and positive aspects to worker’s unions. However, the undeniable benefit to union membership is the collective bargaining power of unions to negotiate with employers to set wages and hours worked.

- The combination of widespread tax cuts, decreased social spending, increased military spending and economic deregulation, collectively, has come to be known as “Reaganomics” or “trickle-down” economics. These were economic policies popularized by President Reagan in hopes that employers would share the wealth they generate through these policies with their employees (11). Trickle-down economics is another much debated topic among economists. Whether employers share earnings generated with their employees or keep it for themselves is a point of contention.

- The logical progression of Reaganomics is the current concept of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism can be defined as a form of liberalism with a focus on free market capitalism. It has been associated with increased globalization, outsourcing of jobs into markets which are less costly to employers and further deregulation of industry. The concept of neoliberalism was popularized by President Clinton through his deregulation of financial markets via the repeal of the 1932 Glass-Steagall Act and passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (12).

Economic stress generated through insufficient capital

If someone’s financial burdens exceed the amount of money he/she takes in through income, this creates economic stress. As a result, he/she has insufficient capital to participate in the economy. This leads to:

- Reliance on credit. As of April 2019, national credit card debt amounted to $1.06 trillion. That amounts to nearly $5,554 per cardholder. In addition to this, credit card delinquency rates of 30 days or more have been recently trending up after falling for years (13).

- Reliance on public assistance such as welfare and supplemental nutrition programs. Most enrollees in these programs are employed yet do not make enough income to cover living expenses (14).

- Increased risk of falling victim to predatory lenders. Predatory loans typically have high interest rates and fees which trap victims in a cycle of debt.

These issues are compounded by the rising amount of student loan debt caused by the ever-increasing cost of college and graduate education. As of the first quarter of 2019, national student loan debt had surpassed credit card debt amounting to nearly $1.49 trillion. That’s about $31,172 per person (15). This initial debt burden serves as an albatross around the neck of graduates and makes it even more likely for them to rely on credit/public assistance. It also makes it more likely for graduates to wind up as employees instead of creating their own businesses due to their debt burden.

The effect of economic stress on psychological health

There is an opposing dynamic between emotional stress and a person’s emotional resilience. No one person has infinite emotional resilience since no one is made from steel. However, a person becomes more resilient through his past experiences and hardships. When emotional stress surpasses a person’s resilience and ability to cope, stress begins to effect that person’s psychological health. Depending on a person’s psychological predisposition, excess emotional stress may result in anxiety-depression disorders or precipitate psychiatric illness (such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder). Sustained emotional stress is more likely than temporary emotional stress to effect a person’s psychological health.

The effect of economic stress on cardiovascular health

Understanding the effect of emotional stress on cardiovascular health is a little more nuanced and requires an understanding of the physiological mechanisms behind the body’s stress response. Stress promotes activity of the sympathetic arm of the autonomic nervous system. As part of the sympathetic response, hormones such as epinephrine, norepinephrine and cortisol are released which all serve the purpose of promoting a “fight-or-flight” response to maximize performance in the end-organs they effect. For example, in a sympathetic response, a person’s heart rate, blood pressure and cardiac output all go up to promote blood supply to vital organs. A person’s respiratory rate will go up to increase oxygen uptake into the blood. The body will mobilize nutrient stores, such as glucose and lipids, in order to keep sources of energy ready at hand, etc. However, a problem arises when a person is chronically stressed and stress hormone levels are chronically elevated.

On a macro level, problems can arise when a person’s blood pressure is chronically elevated. Chronic elevations in blood pressure impede the heart’s ability to pump blood. As a result, the heart muscle hypertrophies in order to compensate for the increased pressure that it’s pumping against. However, a hypertrophied heart doesn’t pump blood efficiently. This can result in heart failure and disruption of the normal electrical conduction in the heart, leading to arrhythmias. A specific type of myopathy, known as Takotsubo’s or stress-induced cardiomyopathy, is related to increased adrenergic signaling of the heart due to stress. Chronic elevations in blood pressure also increase the likelihood for aneurysm formation/rupture and stroke.

An increase in heart rate heightens the oxygen demand on the heart. As a result, it can result in heart tissue ischemia and infarct. Ischemia and infarct are more likely to occur if there is an underlying structural problem such as myopathy or carditis. A 1984 study by Deanfield et al. examined myocardial perfusion (via rubidium-32 uptake), ST segment changes and angina symptoms in response to a variety of stressors. The study observed psychological stressors were indeed as consistently evocative of myocardial perfusion changes as exercise. However, those exposed to the psychological stressor were less likely to self-report angina or experience ECG changes (16).

On a micro level, chronically elevated cortisol levels impede glucose transport into peripheral tissues. It achieves this through disruption of the transport of the insulin-dependent glucose transporter channel, Glut-4, to the cell membrane. In doing so, it induces a state of functional insulin resistance. Cortisol and epinephrine promote gluconeogenesis in the liver and lipolysis in peripheral fat tissue respectively. Cortisol also promotes lipogenesis resulting in increased biosynthesis of cholesterol and fatty acids. As a result, chronically elevated stress hormone levels are associated with elevated blood glucose, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

Finally, persistent stress causes chronic elevation of acute phase reactants, such as D-dimer and various inflammatory cytokines. Inflammatory cytokines increase the likelihood of inflammatory vascular damage. Alongside elevated levels of glucose, LDL and triglycerides, this increases the likelihood of plaque buildup (atherosclerosis) and coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease.

D-dimer is a pro-coagulant factor associated with increased likelihood of embolization causing thromboembolic disorders. In 2004, Central Nigata, Japan was struck by 3 strong earthquakes and 90 subsequent aftershocks. This forced many residents to evacuate their homes and sleep in their cars. The chronic stress alongside immobilization from sleeping in their cars led to a dramatic increase in the incidence of pulmonary embolism (17).

The effect of economic stress on immune health

Stress has been shown to alter the body’s response to infectious disease. Immune cells all have receptors for a variety of cytokines as well as toll-like receptors. B lymphocytes contain membrane-bound cell surface immunoglobulins which bind antigen. T lymphocytes contain specific T cell receptors which bind antigen presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) by antigen presenting cells. Both are involved in adaptive immunity. The natural killer cells and the leukocytes of myeloid lineage, such as neutrophils and macrophages, are in turn responsible for innate immunity. Ongoing research purports there to be expression of adrenergic receptors on immune cells which help modulate immune response. However, this is yet to be fully elucidated.

The mechanism of how stress impairs immune health is not yet fully understood. One of the hypothetical models seeking to address this connection purports there to be a give-and-take relationship between T helper cell subtypes Th1 and Th2 immune responses. This Th1-to-Th2 shift is modulated by adrenergic alteration of the patterns of secreted inflammatory cytokines. The Th1 immune response is involved in combatting intracellular infection and neoplastic disease. The Th2 immune response is involved in combatting extracellular pathogens, such as bacteria and parasites, via activation of B cells and antibody production. Because of this, the chronic adrenergic stimulation of a Th1-to-Th2 shift may result in increased vulnerability to infectious, neoplastic, autoimmune and allergic disorders (18).

The effect of economic stress on thyroid function

Previous studies have linked increased cortisol to suppression of TSH release from the anterior pituitary gland by disrupting the hypothalamic-pituitary axis. A study by Samuels et al. sought to determine fasting TSH levels by using hydrocortisone infusion to mimic cortisol release during stress. By doing so, the study did indeed determine that thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels decreased with hydrocortisone infusion (19).

Cortisol also blocks an enzyme found in peripheral tissues known as thyroid hormone 5'deiodinase. This enzyme is responsible for converting T4 to the active T3 thyroid hormone. T4 hormone is the form of thyroid hormone which is found circulating in the blood. However, it needs to be converted to the active T3 in order to have an effect on target organs. By blocking conversion of T4 to the active T3, cortisol blocks thyroid hormone action. This mechanism is exploited by doctors during treatment of the condition “thyroid storm.” Alongside beta blockers to block thyroid hormone effect on the heart and thioamides to block synthesis of thyroid hormone, glucocorticoids are given to block peripheral deiodination.

The two aforementioned effects of cortisol on the thyroid hormone axis can result in a functional hypothyroidism if cortisol levels remain chronically elevated.

The result of interventions to mitigate economic stress

Workplace intervention to address health outcomes have become common place in today’s world. For example, many workplaces have installed gyms in order to curb the incidence of obesity. Also, many workplaces stock healthy foods to promote healthy eating. But what happens when workplaces address economic stressors?

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health purported that a $1 increase in the minimum wage resulted in a 3.4–5.9% decrease in the suicide rate among adults age 18–64 with a high school education or less. In addition, this effect was pronounced in areas with higher unemployment levels (20). From the data derived by this study, it is fairly clear that economic security decreases stress and improves mental health outcomes. It is also reasonable to infer that economic security would similarly improve cardiovascular and immune health outcomes as well. However, formal systematic analysis would be needed to definitively determine this.

Despite these benefits, employers may be hesitant to address workplace economic stressors due to perceived notions that raising worker’s wages and cutting worker’s hours would result in decreased revenue. However, a 2019 case scenario proves this notion to be false. Microsoft’s Japan subsidiary experimented with a 4-day work week without cutting worker salaries. What resulted was a 40% boost in productivity (21). The reasoning behind this is fairly obvious. When workers aren’t tired or stressed out, they can dedicate more energy to their employment and optimize their performance. However, again, formal systematic analysis would be needed to definitely determine this.

Discussion

Low wages and high number of hours worked in 2020 can largely be attributed to the economic and political influence of corporations in U.S. politics over, roughly, the past fifty years. Though extracting as much productivity as possible for little pay is beneficial for employers, it causes undue emotional stress in their workers. This results in adverse psychological, cardiovascular and immune health outcomes. The most obvious remedy to improving the welfare of American workers is to cut off the corporate money in U.S. politics. This corporate money has essentially turned the political realm into an open auction for influence peddling. Achieving this would require mobilization and advocacy among the U.S workforce. Advocacy for increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour (the “living wage”) would also be a step in the right direction. Employers should strongly consider for their workforce a reasonable increase in pay and decrease in hours worked. Emotional stress caused by economic uncertainty and exhaustion from long hours decrease the productivity and enthusiasm of the workforce. Reasonable measures to address these stressors would go a long way to boost the workplace performance of workers and benefit public health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp-20-20). The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Stress at the workplace [Internet]. World Health Organization. World Health Organization; 2010 [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/

- Doyle A. List of Federal and State Minimum Wage Rates for 2020. [Internet]. The Balance Careers; 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available online: https://www.thebalancecareers.com/2018-19-federal-state-minimum-wagerates-2061043

- Fowardist. A brief history of the 8-hour workday, which changed how Americans work. [Internet]. CNBC; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2017/05/03/how-the-8-hour-workday-changed-how-americans-work.html

- The Productivity–Pay Gap [Internet]. Economic Policy Institute. [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://www.epi.org/productivity-pay-gap/

- Drutman L. How Corporate Lobbyists Conquered American Democracy [Internet]. The Atlantic; 2015 [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available online: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/04/how-corporate-lobbyists-conquered-american-democracy/390822/

- Lindbloom MI, Terranova MK. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission [Internet]. Legal Information Institute. Legal Information Institute; [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/cert/08-205

- Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1 (1976) [Internet]. Justia Law. [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/424/1/

- U.S. Department of State. Available online: https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/nixon-shock. Accessed January 23, 2020.

- NLRB.gov. NLRB; [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available online: https://www.nlrb.gov/about-nlrb/who-we-are/our-history/1947-taft-hartley-substantive-provisions

- Gunn D. What Caused the Decline of Unions in America? [Internet]. Pacific Standard. 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://psmag.com/economics/what-caused-the-decline-of-unions-in-america

- Kenton W. Reaganomics [Internet]. Investopedia. Investopedia; 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/reaganomics.asp

- Fisher JA. Coming Soon to a Physician Near You: Medical Neoliberalism and Pharmaceutical Clinical Trials. Harvard Health Policy Rev 2007;8:61-70. [PubMed]

- Average U.S. Credit Card Debt Statistics 2019 [Internet]. CreditCards.com. 2020 [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://www.creditcards.com/credit-card-news/credit-card-debt-statistics-1276.php

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/mostworking-age-snap-participants-work-but-often-in-unstable-jobs

- Kmcnulty. U.S. Average Student Loan Debt Statistics in 2019 [Internet]. Credit.com. 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 20]. Available online: https://www.credit.com/personal-finance/average-student-loan-debt/

- Deanfield JE, Kensett M, Wilson RA, et al. Silent myocardial ischaemia due to mental stress. Lancet 1984;2:1001-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watanabe H, Kodama M, Tanabe N, et al. Impact of earthquakes on risk for pulmonary embolism. Int J Cardiol 2008;129:152-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 2004;130:601-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Samuels MH, McDaniel PA. Thyrotropin levels during hydrocortisone infusions that mimic fasting-induced cortisol elevations: a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:3700-4. [PubMed]

- Kaufman JA, Salas-Hernández LK, Komro KA, et al. Effects of increased minimum wages by unemployment rate on suicide in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health 2020;74:219-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eadiccio L. Microsoft experimented with a 4-day workweek, and productivity jumped by 40% [Internet]. Business Insider; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/microsoft-4-day-work-week-boosts-productivity-2019-11

Cite this article as: Ratna HN. The effect of economic workplace stressors on health outcomes. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2020;4:26.