A brief report of implementation of a physician citizenship committee in a community hospital to address disruptive physician behavior

Introduction

Physician behavior, communication and professionalism are directly tied to successful patient care in the hospital setting. When medical errors occur, review of the event often uncovers opportunity for improvement in communication, or reveals physician behavior that contributed to missed diagnosis, therapeutic error and other suboptimal care. Research has shown that communication is the most commonly reported root cause for sentinel events (1). Inability to effectively listen and communicate with patients, driven at times by unprofessional behavior, can quickly derail the diagnostic and treatment process, leading to error, increased costs and patient harm (2). Cognitive and affective errors are common during the diagnostic process and interactions with patients and families, driven at times by fundamental attribution error and provider overconfidence (2,3). Disruptive physician behavior and poor physician-patient communication have been connected to many cases of patient injury and poor quality of care (4,5). Malpractice claims data also suggest diagnostic error is the most commonly cited factor contributing to lawsuits and indemnities paid (6) and lack of professionalism can increase risk of lawsuits when there is a misdiagnosis or poor outcome. Some healthcare organizations have institutional cultures that allow physician behavioral issues to persist and affect patient safety, with challenges in accountability, professional standards and workplace morale. Diagnostic error, manifested by delayed or wrong diagnosis—as well as tolerance of poor quality performance in other areas—are more common in such struggling healthcare systems (7).

Methods

We describe the implementation of a program at our community hospital in Northern California of more than 600 staff physicians to address a crisis of professional culture and proliferation of complaints about physician behavior. The Physician Citizenship Committee (PCC) was developed as a multi-disciplinary approach to address concerns raised by patients, nurses and other hospital staff in a non-judgmental, supportive and expeditious manner, and was modeled on a field report previously published (8). Prior to rollout of the project, our hospital had in excess of 50 unaddressed “incident reports”, many of them serious accusations of harassment, use of profanity and name-calling, and other unprofessional behavior with patients and staff. Some of these incidents were connected to patient harm events, and the previous process of addressing these was left to the discretion of the department chairs, resulting in poor accountability and variable timeliness.

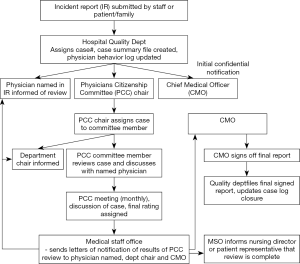

The flowchart of PCC review of physician behavioral complaints is detailed in Figure 1. Emphasis was made on confidentiality of these complaints, and a professional, non-judgmental approach to case reviews. Department chairs were made aware of complaints about physicians in their departments at the outset of the process, and their input was considered in review of the cases. Cases were distributed to individual PCC members, who met privately with named physicians, or discussed by phone. Information from these meetings was used to guide discussion in monthly PCC meetings for review and rating of the cases. Cases were rated simply as “not disruptive behavior”, or disruptive behavior of minor or major severity. In certain instances of repeated complaints, or egregious behavior, physicians were asked to come to the PCC meeting and discuss complaints with the entire committee.

Results

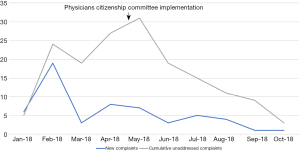

The PCC established a group of seven physicians, with representation from multiple departments, and a mix of gender and backgrounds. Confidentiality of process was made a top priority, with emphasis on clear communication with accused physicians and department chairs. We established monthly meetings for review of complaints, with regular reports to our Medical Executive Committee and Chief Medical Officer. Since initiation of this process, we’ve been able to address and close 95% of complaints within 2 months (see Figure 2), and two physicians were removed from the medical staff due to repeated severe unprofessional behavior. We have also noted a significant decrease in reported events over the 6 months since implementation, with qualitative improvement in relations between nursing and physicians. Concurrently, giving physicians a mechanism for them to address nursing quality and professionalism concerns was key to success and adoption of this project by the medical staff.

Discussion

When a culture of poor physician behavior and lack of accountability exists, it can have direct negative affects on patient care and safety outcomes, including increased rates of medical error and reduced patient satisfaction (9). In addition to case reports and local experience, a large cohort study was recently published that suggested an association of increased surgical complications for patients whose surgeries were performed by surgeons with more coworker complaints of unprofessional behavior (10). Our experience suggests that professionalism can be addressed by a motivated medical staff’s adoption of a PCC framework to address complaints, with rapid improvement in culture and accountability. Complaints can be addressed in a more consistent and expeditious fashion, with significantly less variability in approach and timeliness. As opposed to peer review of medical care with often requires expertise in a given field, expectation for professionalism and high behavioral standards are universal throughout specialties. This allows a diverse group of physicians to share the workload and process of improvement, to drive culture change and reset behavioral expectations when needed. Disruptive physician behavior is also a spectrum, and for most cases, proctoring and coaching can be offered to improve performance, with only the rare cases requiring removal from the medical staff.

Disruptive physician behavior, while important, is only one of several components that can affect quality of patient care and a culture of safety in a hospital. With review of many of these incident reports, we have noted that suboptimal physician communication and episodes of confrontation are often precipitated by other causative factors, such as lack of resources, deficits of nursing quality and professionalism, technology frustrations and electronic health record shortcomings, among others. At times, specific patient factors and challenges contribute as well. While not excusing disruptive behavior by physicians, often there are at least two sides to the complaint, and institutional investment to address these other contributing factors is critical to move a hospital towards a “just culture”—to restore or establish both accountability and trust in the organization (11). In contrast, organizations that tend to take a one-sided or punitive approach with disruptive behavior to punish “bad apples” will risk alienating their medical staff and failing to address these other significant system issues that compromise patient care quality. Some have argued that recidivist physicians, with multiple complaints may not represent the most dangerous behavioral situations with regards to patient safety. These individuals may have personality and communication weaknesses that lead to repeat complaints—as opposed to physicians who have single complaints, where these deficiencies may be less common (12). Individuals with single complaints may signal more significant system weaknesses—such as a shortage in resources or stressful work environment, or inadequacies in support staff—and may actually represent the greater threat to patient safety (12). As noted, struggling organizations will often have multiple needs, suffering commonly from poor organizational culture, inadequate infrastructure, lack of a cohesive mission, system stressors and shocks and dysfunctional external relations with other healthcare entities (7). However, one should also not underestimate the corrosive effect that a recidivist staff member can have on staff morale and work environment, if the issues are left unaddressed.

Engaging physician champions for involvement in a PCC and modeling professional behavior are key elements to success as well (13). Identifying physician leaders who are enthusiastic and passionate to drive change is important, and a balance of perspectives when building such a committee will increase likelihood of success and improve engagement by various groups on the medical staff. A balance of departments, specialties, physician seniority, gender and ethnic background was helpful for our medical staff of diverse physicians. Support from hospital administration was instrumental as well, but fundamentally we felt this endeavor would only be successful and supported by the medical staff if it was a physician designed and led process. Dedicating adequate time and attention during a medical executive committee meeting to review the quantity and severity of physician behavioral complaints was also key to creating momentum to successfully launch this project.

For organizations under financial duress, a commitment to reducing disruptive behavior and improving professionalism is an effort that requires a relatively small investment of financial resources. It is also an opportunity for physicians to lead by example, creating organizational accountability and model a team approach that can really be a professional example to nurses, administration and other healthcare workers, as well as other local institutions. Disruptive behavior among nurses is common as well, and can adversely affect patient outcomes (14). Without acknowledgment of the barriers to communication that disruptive behavior and hierarchical culture create, medical errors propagate within an organization. Team members will not speak up, and patient safety is eventually compromised (15).

We have also noted a prophylactic effect with the establishment of the PCC at our institution, similar to prior report (8). Reports became less common with time and familiarity with the process, perhaps because of the establishment of an effective and timely mechanism to address physician behavior, with physicians wanting to avoid having to answer for these complaints. Previously with unaddressed incentive reports, there was little incentive to change behavior, and we share departmental statistics with our medical executive committee on a monthly basis.

Future directions at our institution include more formalized mechanisms for nursing behavioral accountability and efforts to improve dialogue and communication between caregivers to reduce diagnostic and other medical error events, and improve patient outcomes and satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp.2019.11.01). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- O’Leary DS. Improving America’s Hospitals: The Joint Commission’s Annual Report on Quality and Safety, 2007. The Joint Commission [published November 2007, accessed 15 October 2019]. Available online: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2007_Annual_Report.pdf

- Croskerry P, Cosby KS, Graber ML, et al. Diagnosis: Interpreting the Shadows. 1st edition. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 2017.

- Howard J. Cognitive Errors and Diagnostic Mistakes: A Case-Based Guide to Critical Thinking in Medicine. 1st edition. Berlin: Springer, 2019.

- Johnson JK, Haskell HW, Barach PR. Case Studies in Patient Safety: Foundations for Core Competencies. 1st edition. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Learning, 2016:175-218.

- Rosenstein AH, Naylor B. Incidence and Impact of Physician and Nurse Disruptive Behaviors in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med 2012;43:139-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hanscom, R. Using Malpractice Claims Data to Improve Patient Safety. Coverys, Inc. [published 17 January 2017, accessed 15 October 2019]. Available online: https://www.coverys.com/Knowledge-Center/Using-Malpractice-Claims-Data-to-Improve-Patient-S

- Vaughn VM, Saint S, Krein SL, et al. Characteristics of healthcare organizations struggling to improve quality: results from a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:74-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Handler M. Field Report: An Effective Approach to Disruptive Behavior. Physician Leadersh J, American Association for Physician Leadership [published 2 January 2018, accessed 15 October 2019]. Available online: https://www.physicianleaders.org/news/field-report-an-effective-approach-to-disruptive-behavior

- Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Invited Article: Managing Disruptive Physician Behavior: Impact on Staff Relationships and Patient Care. Neurology 2008;70:1564-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper WO, Spain DA, Guillamondegui O. Association of Coworker Reports About Unprofessional Behavior by Surgeons With Surgical Complications in Their Patients. JAMA Surg 2019; [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dekker S. Just Culture: Restoring Trust and Accountability in Your Organization. 3rd edition. >Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 2017:33-77.

- Frangou C. Disruptive Behavior Mostly Arises From Systemic Causes, Study Finds. General Surgery News [published 2 July 2019, accessed 15 October 2019]. Available online: https:/www.generalsurgerynews.com/In-the-News/Article/07-19/Disruptive-Behavior-Mostly-Arises-From-Systemic-Causes-Study-Finds/55364

- Joshi M, Erb N, Zhang S, et al. Leading Health Care Transformation: A Primer for Clinical Leaders. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 2016:44-6.

- Stewart K, Wyatt R, Conway J. Unprofessional Behavior and Patient Safety. Int J Clin Leadersh 2011;17:93-101.

- Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Disruptive Behavior and Clinical Outcomes: Perceptions of Nurses and Physicians. Am J Nurs 2005;105:54-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: McBeth BD, Douville A Jr. A brief report of implementation of a physician citizenship committee in a community hospital to address disruptive physician behavior. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2019;3:31.