Hospital management and health policy—a South African perspective

Introduction

South Africa is a middle-income country with a gross domestic product (GDP) of US $348 billion in 2017 (1). Economic growth has slowed down over the past 4 years, which influences poverty, unemployment, and inequality. The government has used legal, structural interventions, social programmes and fiscal policies to support redistributive measures but poverty, inequality and unemployment constitute a triple socioeconomic burden in South Africa (2). More than two decades after the advent of democracy, and despite its upper middle-income level status, South Africa remains one of the most unequal countries in the world (3). A World Bank report commissioned in 2016 (4) reported that inequality had worsened during the democratic period.

The South African healthcare system is designed on a free market model that encourages those with means to purchase insurance by joining not-for-profit medical schemes. Medical schemes purchase health services for their members from private health care providers. Uninsured South Africans access healthcare services through public sector healthcare facilities funded from general taxes. Around 16% of the population (8 million people) are medical scheme members while a further 25% of uninsured people pay out of pocket for private-sector care (5). A ranking of quality of care of 48 countries in 2008 ranked care in the public sector 40th while private care was ranked sixth (6). Multiple factors contribute to the difference in quality of care between services provided in the public and private sector including:

- Financial resources: the annual per capita expenditure on health in the private sector is estimated to be around $1,400 while expenditure per capita in the public sector is estimated at $140 (6).

- Distribution of key healthcare providers: the distribution, especially of doctors, between the public and private sector is difficult to determine due to lack of reliable data and public sector employment practices that allow limited private practice for public sector doctors (6).

- Growth of the private hospital sector: until the 1980’s private hospitals were predominantly not-for-profit established by mining houses and faith-based institutions. As such uninsured and insured patients accessed racially segregated public sector hospitals. In the 1980’s, government pro-privatisation policies saw the rapid growth of for-profit private hospitals (7). The racial desegregation of government hospitals in the early 1990’s further stimulated the growth of private hospitals and saw an exodus of medical specialists and other professions to service this industry.

- Disease burden: South Africa has a quadruple burden of disease including diseases linked to poverty; chronic diseases, injuries, and HIV/AIDS (8), The uninsured population (80% of the population) bears a disproportionate amount of this disease burden—South Africa has the largest number of people living with HIV in the world.

- Management models: in the private sector management has been professionalised while the public sector predominantly still embraces an amateur management model with healthcare professionals filling managerial positions. This model is often imposed by regulation e.g., a requirement that clinic managers must be nurses. A political patronage system (cadre deployment) that rewards party loyalists with managerial appointments undermines management efficiency and protects managers from being held accountable. The fact that all managers and healthcare providers in the public sector are members of government sponsored medical schemes, and as such never have to use the services they manage or provide likely contributes to poor quality services (9).

Policy evolution

Since the advent of democratic government in 1994 there have been multiple policy documents and directives published by the Government and National Department of Health. This section tries to give the reader a sense of the extent of this policy development. An immediate step in 1994 was the Government’s Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) (10), which set out broad principles and strategies for development in all sectors to deal with the challenges and lack of services experienced by the majority of South Africans.

The country’s rights-based Constitution, promulgated in December 1996 (11), addressed the key themes of the RDP. Section 27 of the SA Constitution contains the Bill of Rights that obliges the government to ensure the rights of all citizens to have access to health care services, including reproductive health within available resources and that no-one is refused emergency medical treatment. Section 28 of the Constitution promotes and protects the right of children to basic health care services.

The White Paper, Transforming Public Service Delivery was published in 1997 by the Department of Public Service and Administration (12). This espoused the eight Batho Pele (people first) principles, that citizens should be consulted about the level and quality of public services. The other principles are: setting service standards; increasing access; ensuring courtesy; providing information; openness and transparency; redress and value for money. (Note: a white paper in the South African context either sets out a policy at national or provincial level or provides a framework for consultation that informs legislation).

The White Paper for the Transformation of the Health System in South Africa, released in 1997 (13) operationalised the health components of the RDP. The White Paper stated:

- The health sector must play its part in promoting equity by developing a single, unified health system;

- The health system will focus on districts as the major locus of implementation, and emphasise the primary health care (PHC) approach;

- The three spheres of government, NGOs and the private sector will unite in the promotion of common goals;

- The national, provincial and district levels will play distinct and complementary roles.

In 2003 the National Health Act (14) provided a framework for a structured and uniform health system in South Africa with the intention of realising the rights set out in the Constitution. It set out the laws governing national, provincial and local government for health services and the State’s duty to address the right of all to have access to health care services. The predominant focus of all these policy reforms with regard to hospitals was on the public sector.

There followed several policy initiatives focusing on the clinical services provided to patients. For example, a Patients’ Rights Charter and the development of an essential package of Primary Health Care services, including norms and standards for equipment and treatment. This was supported by a Clinic Supervisor’s Manual to ensure the quality of primary health care delivery.

In 2011 the National Department of Health introduced a set of National Core Standards for Health Establishments in South Africa (15). There were seven domains: Patient Rights; Patient Safety, Clinical Governance and Care; Public Health; Leadership and Corporate Governance; Operational Management; Facilities & Infrastructure. Road shows were held across the country to introduce the standards to healthcare workers. Provincial departments of health were tasked with ensuring the implementation of the standards in all public healthcare facilities. The following year a Green Paper on the introduction of the National Health Insurance scheme (NHI) was released which linked re-imbursement and facility accreditation to quality standards.

The promulgation of the National Health Amendment Act in 2013 (16) gave rise to the Office of Health Standards Compliance (OHSC) as an independent regulator of health services with the mandate to protect and promote the health and safety of users of health services by:

- Monitoring and enforcing compliance by health establishments with norms and standards prescribed by the Minister of Health in relation to the national health system.

- Ensuring consideration, investigation and disposal of complaints relating to non-compliance with prescribed norms and standards for health establishments in a procedurally fair, economical and expeditious manner.

The National Core Standards were reviewed and adapted to create a regulatory framework that could be used to assess all health establishments, both public and private, during formal inspections. The first regulated standards were published in the Government Gazette in February 2018 (17) and cover the following areas:

- User Rights;

- Clinical Governance;

- Clinical Support Services;

- Governance and Human Resources;

- General Provisions, which include Adverse Events and Waiting Times.

The OHSC is finalising the assessment tools to enable its inspectors to carry out the regulatory inspections of all health establishments in the country every 4 years.

Current policy issues

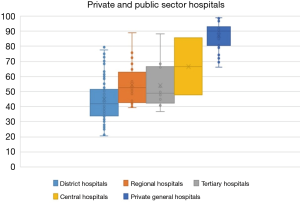

The most pressing policy issue in 2019 is the need to provide universal health coverage through the implementation of the NHI. The Government published a White Paper in 2015 which described three-phases of implementation over 14 years (18). This includes the policy to transition from funding on a free-market system to a single purchaser NHI scheme. The first phase, from 2012/2013 until 2016/2017 for strengthening the public health system and setting up the regulatory body, the OHSC. In its monitoring role of health establishments, the OHSC conducted ‘mock’ inspections, as the regulations had not been promulgated. Six hundred and ninety-six public health establishments were inspected in 2016/17 and 923 in 2017/18 of the 3,186 public health establishments in the country. The findings of these inspections were published in the OHSC Annual Inspection Report in June 2018 (19). (Figures 1-3 below are from the report). Thirty-eight percent of the establishments inspected complied with 50% or more of the standards. See Figure 1.

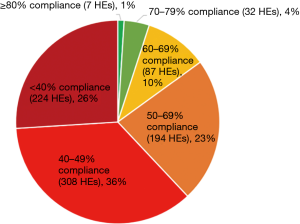

A further breakdown of the information looked at the average standard compliance scores by facility type. The target is a minimum of 80%. See Figure 2.

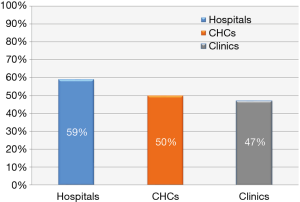

Of the facilities inspected and analysed, 1 was a central hospital, 2 provincial tertiary hospitals, 12 regional hospitals and 35 District hospitals with an average outcome score of 59%; 34 Community Health Centres scored an average of 50% and 768 clinics scored an average of 47% (19).

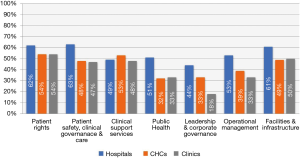

Figure 3 below, indicates that of 7 domains, the domain Patient Safety, Clinical Governance and Care average performance score for hospitals was 63%. The lowest average performance score for hospitals was for the domain on Leadership and Corporate Governance which had a score of 44%.

Now that the regulatory standards for all health establishments are available, the OHSC will commence the regulatory inspections of all health establishments in the country in 2019. The strengthening of the public health sector is far from complete. The National Department of Health Annual Performance Plan 2016/17–2018/19 states that a key policy initiative will be to facilitate the implementation of NHI, by developing systems for provider payments, patient registration and health provider registration as well as systems to mitigate fraud and risk (20).

Proposed amendments to the Medical Schemes Act, which governs how medical aid schemes are funded, administered and can charge, have also been released for consultation.

The timetable towards migrating the funding of health care from the current free-market model to a National Health Insurance (NHI) model is however uncertain as the Minister of Finance in his most recent [2019] budget speech announced that some of the funds set aside to fund the implementation of the NHI will be diverted to deal with critical staff shortages over the next 3 years. Additional funding will be put to developing information systems to develop the patient registration system and to centralise the dispensing and distribution of chronic medication to more than three million users (21).

Hospital management

The White Paper on the Transformation of the Health System published in 1997 (13) set out bold steps to improve the management of hospitals. It was recognised that most public hospitals were poorly managed because the hospital managers only had limited authority and the management systems and structures were inappropriate. There were limited numbers of skilled managers and limited responsibility and authority were accorded to hospital managers. The response to these challenges was to decentralise hospital management to promote efficiency and cost effectiveness. The intention was that provincial departments of health would delegate decision making to hospital managers for personnel, procurement and financial management to improve the control in managing daily operations. The caveat was that such delegations would depend on the capacity of the manager to take on such responsibilities. The view was that over time, hospital managers would have authority for all personnel issues and ultimately be responsible for human resource planning, staffing establishments, training and labour relations.

The White Paper proposed the introduction of a general management system based on cost centres and functional units—much like the model introduced in the British National Health System with the purchaser-provider split in the 1980s. To achieve this, the existing centralised systems needed to be completely overhauled. The emphasis was on the need for effective training and development programmes for senior and middle managers.

With some notable exceptions, most of the intentions set out in the White Paper did not happen. Human resource planning and recruitment remained at the provincial level. The financial delegations to hospital managers did not give them budgetary control and an active labour movement ensured that national level bargaining on pay and conditions was retained. Professionalisation of management in the public hospitals has thus not fully been achieved.

As a result, major inequalities exist between the public and private hospital sector. Comparisons around access and quality generally indicate better access, quality and patient satisfaction within the private sector. However, there is substantial over utilisation (70.8% caesarian rate compared with an international norm of 24.7%) and fragmentation of care due to a regulatory environment that opposes multidisciplinary practices. Private hospital costs as a percentage of total healthcare expenditure in the private sector is high by international comparison comprising 37% of expenditure (22).

The study by Ranchod et al. compared accreditation survey scores over 14 years between public and private hospitals in the accreditation programme of the Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa (COHSASA) as well as the patient perspective reflected in data from the General Household Survey. The research provides evidence of the polarisation between public and private facilities: private facilities consistently scored above public facilities across a range of accreditation categories, and there was far greater variability in the scores achieved by public facilities. The same polarised relationship was found to hold across key sub-components of the scores, such as management and leadership of hospitals in the two sectors. The accreditation data also highlight key differences between the two sectors across dimensions that relate to patient safety, and therefore cannot be ignored. The low levels of variation in the service element scores for private hospitals point to a consistency in leadership, management, systems and incentives across hospitals. By contrast, the wide range of public-sector scores points to a variety of challenges across regions and levels of hospitals—not least of which are resource challenges. See Figure 4.

The South Africa Competition Commission in 2018 released the results of their health market inquiry (23). This report found that the private hospital market is dominated by three for-profit listed companies Netcare, Life Healthcare and Mediclinic which have a combined market share of 83% of private beds and 90% of admissions. This concentration was flagged as a major competitive constraint, as medical schemes are hampered in their ability to negotiate competitive prices as no scheme can afford to exclude any of the three hospital groups from their provider network. Only two of the medical schemes were deemed large enough to exert buyer pressure. As a result, the private hospital market is characterised by the absence of effective direct competition between the three large hospital groups. The inquiry also raised concerns around the lack of regulation of private hospitals beyond a licencing requirement and the danger of an environment that is conducive of overt and covert collusive conduct. These concerns raise issues for the policy development to ensure the effective implementation of the NHI.

Conclusions

As the country moves towards an NHI system and the inherent purchaser–provider model, it faces considerable challenges. The NHI will require that all health establishments be certified by the OHSC and then accredited by the NHI Fund to be allowed to provide services to patients. Currently the gap between the two sectors remains huge, in terms of physical facilities, equipment and quality of service.

The public sector hospitals host the majority (90%) of the country’s hospital beds but are poorly managed and will struggle to meet OHSC criteria, as can be seen by the results from the 2016/17 mock inspections shown above, where, of concern, the leadership and governance domain scored lowest. The physical fabric of private hospitals is generally of a high standard and they are well managed by a professional group of health managers.

In a political free environment this reality would translate into private hospitals rapidly expanding to service the NHI market. However, the political realities and the strength of public sector unions makes this situation unlikely. The concerns raised by the Market Inquiry also caution against the desirability of such a development. There is an urgent need to focus on creating an environment within the public sector that will rapidly improve the management of public sector hospitals allowing them to meet the requirements of the NHI. To achieve this objective, the following needs to happen:

- The policies that envisaged decentralisation of autonomy to hospital management need to be fully implemented. Public sector hospital management need to be able to manage their budgets, retain income generated, hire and fire staff and in general operate as independent economically viable entities.

- Governance structures, (Hospital Boards) need to be regulated in line with the provisions of the Companies Act that dictates the obligations and sanctions of members of governance structures to ensure that adequate supervision is provided.

- Hospital management needs to be professionalised requiring managers to be able to demonstrate managerial competency. Political interference in appointments must be removed and managers need to be held accountable for the outcomes of the service they manage.

- There needs to be a systematic improvement programme across the health system to ensure good services for patients.

- All health care workers must be accountable for their actions and move to a mindset of continuous improvement rather than compliance, ultimately set a trajectory towards excellence for all.

Acknowledgments

Marilyn Keegan for assistance and editing.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Christine Dennis) for the series “Health Service Management” published in Journal of Hospital Management and Health Policy. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jhmhp.2019.06.01). The series “Health Service Management” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Website: Countryeconomy.com accessed 25.2.2019. Available online: https://countryeconomy.com/gdp/south-africa

- World Bank: Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa: An assessment of drivers, opportunities and constraints. In. Washington D.C.: The World Bank, 2018. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/pdf/124521-REV-OUO-South-Africa-Poverty-and-Inequality-Assessment-Report-2018-FINAL-WEB.pdf. Accessed 25.2.2019.

-

What South Africa Can Teach Us as Worldwide Inequality Grows - UNDP: Human Development Report 2016-Human Development for Everyone. In. New York: UNDP; 2016. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2016_human_development_report.pdf

- Bongani M. Mayosi, Solomon R. Benatar, Health and Health Care in South Africa: 20 Years After Mandela. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1344-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burger R, Christian C. Access to health care in post-apartheid South Africa: availability, affordability, acceptability. 2018. Available online: http://rhap.org.za/wpcontent/uploads/2018/08/access_to_health_care_in_postapartheid_south_africa_availability_affordability_acceptability.pdf. Accessed 2.3.2019.

- Coovadia H, Jewkes R, Barron P, et al. The health and health system of South Africa: historical roots of current public health challenges. Lancet 2009;374:817-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw D, Groenewald P, Laubscher R, et al. Initial burden of disease estimates for South Africa, 2000. S Afr Med J 2003;93:682-8. [PubMed]

- Johnson Mbaso S. Innovation Executive, Foundation for Professional Development, Pretoria. Interview 25 February 2019.

- African National Congress, The Reconstruction and Development Programme: A policy framework. 1994, Umanyano Publications Johannesburg. Available online: https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/the_reconstruction_and_development_programm_1994.pdf

- Republic of South Africa, Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996, Act 108 of 1996. Available online: http://www.info.gov.za

- Department of Public Service and Administration, White Paper on Transforming Public Service Delivery, Government Gazette, # 17910. 1997, National Department of Public Service and Administration: Pretoria. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/183401.pdf

- Department of Health, White Paper for the Transformation of the Health System in South Africa, Government Gazette, # 17910. 1997, National Department of Health: Pretoria. Available online: http://www.doh.gov.za/docs/policy/white_paper/healthsys97_01ht

- National Department of Health: National Health Act No 61 of 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/national-health-act. Accessed 2.3.2019.

- National Department of Health: National Core Standards for Health Establishments in South Africa (2011).

- National Department of Health: National Health Amendment Act No 12 of 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/national-health-amendment-act. Accessed 2.3.2019.

- National Department of Health, Norms and Standards Regulations Applicable to Different Categories of Health Establishments. Government Gazette # 41419. February 2018. Available online: https://ohsc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/Norms-and-Standards-Regulations-applicable-to-different-categories-of-health-establishments.pdf

- Minister of Health. White Paper on National Health Insurance. Government Notice No. 1230, Government Gazette # 39506, 2015. National Department of Health, Pretoria. Available online: https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201512/39506gon1230.pdf

- Office of Health Standards Compliance Annual Inspection Report 2016–2017. Available online: http://ohsc.org.za/wp-content/uploads/OHSC-2016-17-ANNUAL-INSPECTION-REPORT-FINAL.pdf. Accessed 5.3.2019.

- Department of Health. Annual Performance Plan 2016/17 – 2018/19. Available online: http://www.health.gov.za/index.php/2014-03-17-09-09-38/strategic-documents/

- Budget Review 2019 National Treasury of South Africa, 20th February 2019, Communications Directorate, Treasury, Pretoria. Available online: http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/national%20budget/2019/

- Ranchod S, Adams C, Burger R, et al. South Africa’s hospital sector: old divisions and new developments. S Afr Health Rev 2017;1:101-10.

- Health Market Inquiry, Provisional findings and Recommendations Report, 5th July 2018, Competition Commission South Africa, Pretoria. Available online: http://www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Health-Market-Inquiry-1.pdf

Cite this article as: Stewart J, Wolvaardt G. Hospital management and health policy—a South African perspective. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2019;3:14.